Concluded: Walter Weston's guide to alpine activities across the Empire during the 1930s.

Like its adopted parent, Japan,

Korea – now known as Chosen – is a land of mountains. Few of its ranges present, from the technical point of view, serious climbing problems to the mountaineer, and from the point of view of altitude they are not imposing. The highest is the peak known to the Koreans as Faik-tu-san, and to the Japanese as Haku-to-san, i.e. "The White-topped Mountain." and its altitude is some 9,000 feet. The ascent of it was made by Sir Francis Younghusband in 1886 without difficulty. It stands on the Manchurian border of Korea, but presents little interest from the climbing point of view.

|

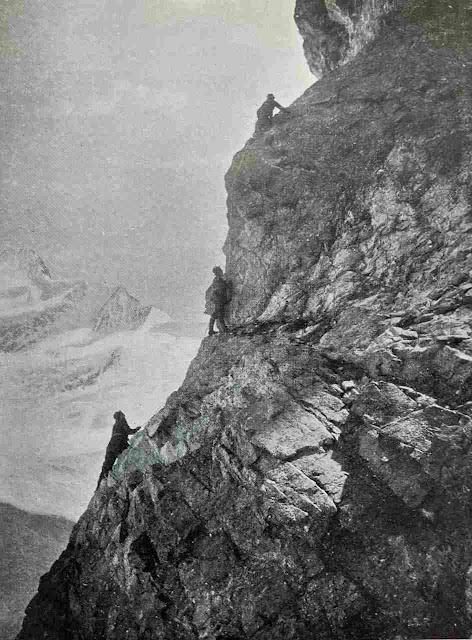

Insupong (Korea): a granite formation.

Original image and title from The Lonsdale Library Mountaineering. |

In spite of the low altitudes, some fine rock-peaks, mostly granite, from 2,000 to 6,000 feet, are to be found in various parts of the country and these mostly afford quite difficult climbing. The best-known group is Kongo San, the "Diamond Mountains," rising about the middle of the north-east coast, comprising an area of about 10 miles square with granite summits ranging up to 5,500 feet. They are famed, among both Japanese and Koreans, for their scenic beauty. The best periods for climbing are spring and autumn and the group is readily accessible by rail and motor-car from Keijo (Seoul), the capital, in less than a day. Keijo itself is on the main railway line from Peking to Japan, and about thirty-six hours by rail and sea from the Japan ports, or about half that time by air. The peaks of Umi Kongo, those nearest the coast, afford the best scrambling. Shusenho (4,450 feet) has several summits, each providing an excellent day’s work.

Climbing of equal excellence can be obtained within a few miles of Seoul, though the heights here are lower. Insupong, a fine, almost egg-shaped peak (2,800 feet), and Bankeidai, the same height with three main summits, offer fine sport. Five miles farther north of Seoul lies Manjoho (2,000 feet), a gigantic tooth offering several routes, all difficult. This is reached by half an hour's motor drive followed by one and a half hour's walk; the ascent is a difficult face climb needing great care. Rather lower but of even greater interest is Goho, the Five Brothers, two of whose five rocky summits are crowned with cube-shaped monoliths probably not yet ascended.

These granite battlemented ridges and towers of Korea in many cases resemble the finest parts of the granite cliffs of Cornwall south of the Land’s End, though much higher. There are no guides available, though stout coolies can usually be obtained as companions to the feet of the rocks themselves. The chief, perhaps sole, European authority is Mr. C. H. Archer, of the British Consulate-General in Seoul, from whom, or from his successor, information and advice would be always willingly afforded. From the headquarters of the Japanese Alpine Club in Tokyo, introductions will generally be furnished to members living in Seoul.

FormosaThe island of Formosa, now known to the Japanese as Taiwan, lies about 500 miles south of Japan proper and some 100 miles east from the coast of China. It is 240 miles long and its greatest breadth is about 80 miles. While its western half and a narrow strip on the south-east are flat and fertile, nearly the whole of the remainder of the island is mountainous and covered with dense forests. It contains at least five of the highest peaks of the Japanese Empire. Of these the loftiest, formerly known to Europeans as Mount Morrison, is Niitaka (12,960 feet), “the new high mountain,” in contradistinction to Fuji-san, hitherto, as its name implies, the highest in Japan. Next comes Tsugitaka, or “next high” (12,897 feet). It was previously entitled Mount Sylvia.

Most of the others are still unknown to the Western world, and some are virgin peaks. As a result of the activities of the Formosan Mountaineering Club, however, new routes are being continually opened up, and it is to the officials of that Club, whose present headquarters are to be found in the Imperial Government Building in Taihoku, the capital, in the extreme north of the island, that intending mountaineers should apply for information. They can be relied upon for every assistance.

It is the dense forests of Formosa that render these peaks difficult of access, while the deep and precipitous valleys by which on the east coast they are approached constitute a further obstacle. Police paths are being constructed, where needed, in every direction, and some of these are wonderful feats of engineering; they are notably in connection with the remarkable East Coast Road.

The “‘timber-line” is approximately 12,000 feet. There is very little snow usually to be found on them, though a certain amount lies on Tsugitaka in ordinary seasons. The best months for climbing are (1) November and (2) May. Owing to the heavy rainfall frequently experienced, some of the police paths, and police posts, and even portions of the great East Coast Road, are liable to damage. Modifications of the following routes may therefore occasionally have to be made, but the Formosa Mountaineering Club, already referred to, will usually be able to help with the latest information, while the police authorities themselves are always courteous and obliging to properly accredited visitors.

It is essential, however, that at least one member of any party of mountaineers should be able to speak English.

Niitaka (12,960 feet) was first ascended in 1896 by Dr. S. Honda and a party of Forestry officials. There are no “technical” climbing difficulties and only the final 2,000 feet require any effort. The two most usual routes are from the north-west, the first (a) lying mainly up a tributary of the Dokusui River, and the latter (b) by the well-known Ari-San light railway, which brings down the timber from the forests of that name.

(a) From the station of Nisui, on the west coast railway, about 100 miles south of Taihoku, a branch line eastwards takes one to the small town of Suiriko in two hours. Then a timber trolley-line mounts in some ten hours to the police post of Tompo, 22 miles distant, at the foot of Niitaka (7,000 feet) and 4,000 feet above sea-level. Hence the road ascends by easy gradients for 14 miles, up a fine valley, to the police post of Hatsūkan, on a shoulder of the mountain. From here it is 2 miles farther on to the police post of Niitaka, from which the summit rises westwards and is gained without difficulty.

The top consists of a rocky platform some 30 feet long on which stands a triangulation post, a small concrete shrine in honour of the Spirit of the Mountains, and a brass indication dial. Four rocky buttresses fall to N., S., E., and W. respectively, on some of which excellent rock-climbing can be found.

The descent by the Ari-San route leads via the police post of Niitaka and that of Taataka 7 miles lower down, together with a journey of some two hours on the Ari-San light railway to the station of Kagi on the west coast main line, about two hours north of Tainan, the southern capital of Formosa.

With the ascent of Niitaka can be combined those of Shūkōran (12,577 feet) and Maborasu (12,487 feet), starting from the police post of Shūkōran, at a height of 9,700 feet. The former will occupy about four hours to the top, and is tedious rather than difficult, but when Maborasu is also included, it may be necessary to bivouac on the saddle between the two peaks before the descent to the police post.

A more interesting region, and one less familiar to Western mountaineers, is that lying to the north-east of the Niitaka group. It has the additional advantage of affording in its approaches the opportunity of seeing something of the wonderful East Coast Cliffs, amongst the most remarkable of their kind in existence. The chief summit of this group is Mount Tsugitaka, “the second highest peak” in the Empire.

Leaving Taihoku early in the morning by the East Coast Railway one goes southward to Ratō and then changes into the light railway serving the extensive forestry works on Mount Taiheizan. This ends at the hot spring of Doba, an excellent stopping-place for the first night.

The next day, with porters obtained here, one mounts to the police post of Pyanansha, and then on the third day to the post of Shikayau at the base of Tsugitaka, over a pass of 6,000 feet. Beyond the summit of the pass stands the police post of Pyanan Ambu with a small shop under police supervision. From Shikayau the route traverses a deep ravine, and finally mounts a tributary of this to the Tsugitaka hut for the night. From here the remaining 2,000 feet to the summit of the mountain, first up the steep rocky bed of a torrent and then over the creeping pine that clothes the slopes. The summit consists of two peaks about a mile apart at either end of a long ridge. To the south it falls away in a series of huge precipices. To the north it stretches in a long serrated ridge of some 5 miles before turning to the east, where it culminates in the peak of Momoyama (11,123 feet). Here another ridge branches to the north-west and ends in the striking peak of Daihenzan (11,722 feet), which affords an interesting climb. More snow is usually found on Tsugitaka than on others of the Formosan mountains yet climbed. With the ascent of Daihasenzan can be combined that of Hapanarau (12,250 feet), now better known by a native name, Shimita, recently adopted by the Formosan Mountaineering Club. A night would have to be spent on the main Tsugitaka ridge on the way.

Descending to the police post of Pyanan Ambu, after two more bivouacs in the open, it is three hours to the police post of Pyanan, which lies 25 miles inland from the East Coast Road.

Between Pyanan and the coast rises a fine range of which Nankotai and Chuosen are the loftiest summits, both well over 12,000 feet.

Nankotaisan (12,460 feet): From Pyanan a climb of 4,000 feet leads to the “savage” hunters’ hut on the lower slopes of Nankotai, a convenient night’s resting-place. Another day is usually needed for the remainder of the ascent to the top, traversing: en route the subsidiary peak of Koshi (12,052 feet). From here one looks across the narrow entrance of a fine amphitheatre to the final arête of Nankotai. There is now a choice of routes to the highest point (12,460 feet), either round the rim of the amphitheatre itself or by descending a long slope of rough scree to its “floor” and then up by the rocks of the opposite side. The upper part of Nankotai is remarkable for the extraordinary quantities of Alpine rhododendrons.

Chuosenzan (12,190 feet): From the camp above-mentioned a long descent leads to the police post of Pyahau (not to be confused with Pyanan already mentioned). Hence a walk of 30 miles along mountain paths takes one down to Sendan, a route remarkable for its evidences of the thoroughness of the manner in which Japan is developing the primitive ‘‘savage’’ population of “‘head-hunters” and their neighbours. Travellers are handed on from one police post to the next. Some of the coastal scenery in the lower part of the descent from Sendan to Kenkai, actually on the East Coast Road, is very striking.

The Road itself is a remarkable feat of engineering, much of it running along the face of cliffs that rise sheer from the sea to a height of 7,000-8,000 feet. At present it links the railway terminus of Suwo in the north with that of Karenko in the south, and is traversed by very efficient services of motor-buses along a distance of some 54 miles.

From Kenkai, at the mouth of the River Takkiri, a motor ride of two miles leads to the police post at the entrance to the Takkiri gorge, up which the first part of the ascent is made, and which is here spanned by a suspension bridge some 450 feet in length. The gorge itself is wild and impressive in the extreme, particularly beyond the police post of Batakan, where a narrow track is hewn out of the face of a precipice 2,000 feet above the stream, with an almost sheer wall of rock stretching 1,500 feet above. The first halting-place for the night is at the important and extensive police post of Tabito (where a kindly welcome is to be counted upon) 16 miles from the entrance to the gorge. The next stage is an easy one of 10 miles up to Tausai, the police post at the base of Chuo-senzan, whence an ascent of some eight hours, through forest, pasture land, and rock of varying degrees of soundness, lands one on the summit by way of a ridge about 2,500 feet in height. Rhododendrons are again seen in profusion near the top of Chuosenzan, as on Nankotai-san.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

JapanRev. Walter Weston, A.C., 1st Honorary Member of the Japanese Alpine Club,

Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps (Murray, 1896).

Rev. Walter Weston,

The Playground of the Far East (Murray, 1918).

Rev. W. H. Murray Walton, M.A.,

Scrambles in Japan and Formosa.FormosaPapers and notes in the Journal of the Japanese Alpine Club (Nihon Sangaku); and in the Journal of the Formosa Mountaineering Club (Imperial Government Buildings, Taihoku, Formosa).

Paper by Rev. W. H. Murray Walton, M.A., in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, June 1933.

KoreaThe Alpine Journal, 43, No. 242, May 1931: “Some Climbs in Korea,” by C. H. Archer (illustrated).

ReferencesFrom Walter Weston's chapter on “Korea”, in Sydney Spencer (editor),

Mountaineering: The Lonsdale Library Volume XVIII, London: Seeley Service & Co, 1934.