So times had changed. We’re now in the Taishō era (1912–26). In these years huts were built, paths were made and guide associations formed. Now everybody could go to the mountains. JAC members started to do pioneer work abroad – notably Maki “Yūkō” Aritsune (1894–1989) on the Eiger’s Mittellegi Ridge in 1921, and on Mt Alberta in 1925.

What were the foreigners doing at this time? Well, some joined the JAC – the club’s records must be very interesting on this topic. According to Hamish Ion, a mountain historian, within a year of the JAC’s foundation there were eleven foreign members (not all of them English) two were Anglican clergymen, like Weston, two were university teachers, and the rest were businessmen in Yokohama, Tokyo and Kobe.

Foreign women too joined: Mrs Frances Weston and Mrs Emily Elwin became members before 1923. Also, two lady missionaries were introduced by your founder member Takano Takazō and Kondō Shigekichi (1883–1969), who had studied at Glasgow University.

Interestingly, when Mrs Weston went back to England, she wasn’t able to join Britain’s Alpine Club – instead she had to join the Ladies Alpine Club founded in 1907 by the hard-driving Mrs Elizabeth Aubrey LeBlond, the pioneer winter alpine climber and mountain photographer. Officially, of course, the JAC did not admit women until 1949 – but this was still a quarter of a century ahead of Britain’s Alpine Club (1974) and the Swiss Alpine Club (1980). This too was pioneer work.

Some foreigners also founded their own association: the Mountain Goats of Kobe, who often trained on Rokkō-san. I’m not sure when the MGK started (some say 1911 as the Ancient Order of Mountain Goats), but its house journal Inaka first came out in 1915 and continued for almost a decade. It was edited by a Kobe resident and oil company employee, H E Daunt.

Daunt was a golfer before he was a mountaineer. As a member of the Kobe Golf Club, the first Japanese golf club, opened in 1913, he won the Japanese amateur championship in 1915. In May 1919, he helped to design Korea’s first-ever golf course, describing his experience in Inaka (1923). Visiting Seoul at the invitation of the South Manchurian Railway Company in May 1919, he helped Mr Inohara, the general manager of the Chosun Hotel, set out the course.

Is it perhaps an exquisite coincidence that there are just 18 volumes of Inaka, like the 18 holes of a golf round?

As you can see, Inaka was well produced – it was printed by a local newspaper company. Alas, even single volumes of Inaka are very rare and expensive - complete sets are even rarer: I only know of two: one in London and one in Kobe – I hope one day it will be reprinted or at least a selection of articles. There is some good stuff in there, for example, an eyewitness account of the 1915 Yake-dake eruption by J Merle Davis, an American missionary, in Inaka Vol II, 1915.

By the way, many, perhaps most, of the leading MGK members were also members of the JAC. And for a number of years after the first world war, H E Daunt edited the English-language supplement of Sangaku, the JAC’s journal.

The MGK were not the only show in town. At one point, more than a third of the members of the Kobe toho-kai (神戸徒歩会) were foreigners, and its journal Pedestrian carried articles in English as well as Japanese. The Kobe toho-kai was founded in 1910 as the Kobe Waraji-kai (神戸草鞋会).

Of course, clubs are never the whole story ...

|

| Maki Yuko returns from the Eiger with his guides, September 1921 |

What were the foreigners doing at this time? Well, some joined the JAC – the club’s records must be very interesting on this topic. According to Hamish Ion, a mountain historian, within a year of the JAC’s foundation there were eleven foreign members (not all of them English) two were Anglican clergymen, like Weston, two were university teachers, and the rest were businessmen in Yokohama, Tokyo and Kobe.

Foreign women too joined: Mrs Frances Weston and Mrs Emily Elwin became members before 1923. Also, two lady missionaries were introduced by your founder member Takano Takazō and Kondō Shigekichi (1883–1969), who had studied at Glasgow University.

Interestingly, when Mrs Weston went back to England, she wasn’t able to join Britain’s Alpine Club – instead she had to join the Ladies Alpine Club founded in 1907 by the hard-driving Mrs Elizabeth Aubrey LeBlond, the pioneer winter alpine climber and mountain photographer. Officially, of course, the JAC did not admit women until 1949 – but this was still a quarter of a century ahead of Britain’s Alpine Club (1974) and the Swiss Alpine Club (1980). This too was pioneer work.

|

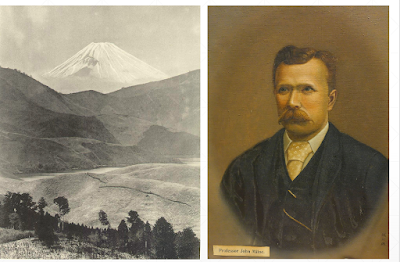

| H E Daunt, the "Bell Goat". |

Daunt was a golfer before he was a mountaineer. As a member of the Kobe Golf Club, the first Japanese golf club, opened in 1913, he won the Japanese amateur championship in 1915. In May 1919, he helped to design Korea’s first-ever golf course, describing his experience in Inaka (1923). Visiting Seoul at the invitation of the South Manchurian Railway Company in May 1919, he helped Mr Inohara, the general manager of the Chosun Hotel, set out the course.

Is it perhaps an exquisite coincidence that there are just 18 volumes of Inaka, like the 18 holes of a golf round?

As you can see, Inaka was well produced – it was printed by a local newspaper company. Alas, even single volumes of Inaka are very rare and expensive - complete sets are even rarer: I only know of two: one in London and one in Kobe – I hope one day it will be reprinted or at least a selection of articles. There is some good stuff in there, for example, an eyewitness account of the 1915 Yake-dake eruption by J Merle Davis, an American missionary, in Inaka Vol II, 1915.

|

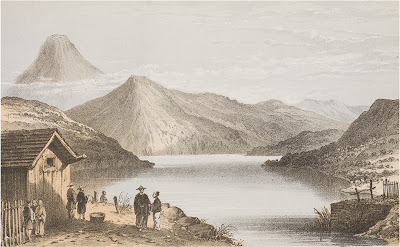

| The eruption of Yake-dake in 1915. |

By the way, many, perhaps most, of the leading MGK members were also members of the JAC. And for a number of years after the first world war, H E Daunt edited the English-language supplement of Sangaku, the JAC’s journal.

The MGK were not the only show in town. At one point, more than a third of the members of the Kobe toho-kai (神戸徒歩会) were foreigners, and its journal Pedestrian carried articles in English as well as Japanese. The Kobe toho-kai was founded in 1910 as the Kobe Waraji-kai (神戸草鞋会).

Of course, clubs are never the whole story ...