Thank you Ishizuka-san and members of the Ryokusōkai for inviting me to speak here at the offices of the storied Japanese Alpine Club – the original idea was to talk about translating Nihon Hyakumeizan (One Hundred Mountains of Japan), but translations can be a dry subject, and so with your help, we settled on the topic of foreign mountaineers in Japan – what they did in the past, what they are doing now, and what they might think of doing in the future.

When I started looking at this topic, I realised that this is a huge field. Quite simply, even if we restrict ourselves to the early days, more foreigners explored the mountains of Japan than can possibly be mentioned, even cursorily, in a one-hour talk. The literature itself is quite sizeable – for example, I haven’t yet managed to lay my hands on a copy of Shōda Hito'o’s magisterial Ijintachi no Nihon Arupusu (Strangers in the Japan Alps).

So – my apologies in advance – I’m afraid that this talk will by no means consult all the available sources; it will skate selectively over the surface. And it will raise more questions than it gives answers. But let us wade in there anyway.

The past

When it comes to the past, there’s no question where we should start. In today’s company, we have to begin with Walter Weston (1861–1940) – here he is with Shiga Shigetaka: together they were the JAC’s first honorary vice presidents.

|

| Shiga Shigetaka and Walter Weston. |

By the way, I was embarrassed to read in the Ryokusōkai’s newsletter that certain senior members of the JAC entrusted Weston with a valuable picture scroll, which they intended as a gift to the British Alpine Club’s president. But, when he went back to England, Weston apparently mislaid this handsome present. This is regrettable in the extreme, and I can only bow deeply in apology on behalf of my countryman.

|

| Kamijo Kamonji (left) and Walter Weston (right). |

To this audience, Weston is so well known that there is no need to rehearse his story in detail. He first came to Japan in 1888. His book Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps (1896) was based on climbs in 1891–93, during which he climbed Yari-ga-take with the pioneer guide Kamijō Kamonji (1847–1917). Then he went home and, in April 1902, he got married.

|

| Kojima Usui and Yari-ga-take surmounted by a surveyor's marker. |

In August of the same year, Kojima Usui, made his famous ascent of Yari – inspired by Shiga Shigetaka’s Nihon Fūkeiron (A theory of the Japanese landscape). Then, in 1903, Kojima discovered that Weston had come back to Japan – actually it was his climbing companion on Yari, Okano Kinjirō, who thought of looking in the Yokohama phone directory. Okano and Kojima met Weston for tea, over which they discussed the idea of an alpine club and an alpine journal in Japan – and the rest is history. In October 1905: the JAC was founded.

For his achievements, Weston is sometimes called the father of Japanese alpinism. But was he really?

Foreigners were climbing in Japan before Weston was even born – a whole generation earlier.

Let us rewind to September 4, 1860: Rutherford Alcock (1809–97), the British emissary, is setting out with seven British colleagues and about a hundred Japanese officials, agents of the bakufu and their attendants with thirty horses. Alcock’s dog, Toby, is going along too.

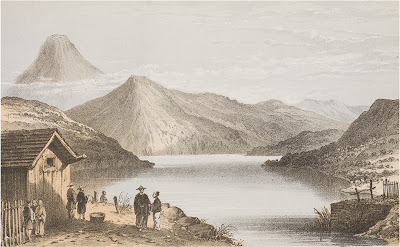

|

| An illustration from Rutherford Alcock's The Capital of the Tycoon. |

Alcock’s main aim was political: to assert his right to travel freely under 1858 treaty. But it wasn’t just about politics. Before he became a diplomat, he had been a surgeon and he liked to have men of science around him. In the party was the botanist and gardener John Veitch (1839–1870). On Mt Fuji, Veitch “discovered” the shirabiso and named it for himself: Abies veitchii.

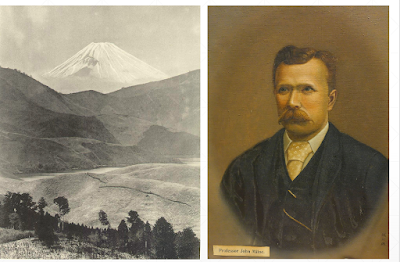

|

| John Veitch and the tree he named for himself. |

On September 11th, they all reached summit of Mt Fuji, where a certain Navy Lieutenant Robinson mistakenly calculated an altitude of more than four thousand metres. Later, alas, at the Atami hot springs the dog Toby strolled over an erupting geyser with fatal consequences. Veitch too died too young, at the age of 31 in England, but you can still visit a garden that he helped to create there…

|

| At "Hakoni": from Rutherford Alcock's The Capital of the Tycoon. |

As only diplomats could move freely at that time, they naturally accounted for the earliest wave of mountaineering by foreigners. Six years after Alcock’s climb, a Swiss diplomat led the second gaijin ascent of Fuji.

|

| The Swiss delegation in Edo: contemporary print. |

This was Caspar Brennwald (1838–99), who later helped to found a trading company that still exists today. The Swiss planned to bivouac on the summit but met with a thunderstorm that forced them to seek shelter in a pilgrim’s hut.

|

| Carl Johann Maximowicz and some of his specimens. |

On the heels of the diplomats came the scholars. The Russian botanist Carl Johann Maximowicz (1827–91) arrived in Japan late in 1860 and, during the next two years, walked from Hokkaido to Kyushu, taking in mountains such as Unzen, Aso and Kujū on the way. Along the way, he must have found a lot of interesting plants: he sent home 72 chests full of specimens – some of which can still be seen in museums today. Another naturalist, the German Wilhelm Dönitz (1838–1912), climbed Nantai and Fuji in 1875, although he was more interested in spiders and millipedes than flowers.

|

| Benjamin Smith Lyman with his team of surveyors. |

Geologists and geographers were no less active. In 1874, Benjamin Smith Lyman (1835–1920), an American mining engineer and surveyor, explored the Daisetsuzan while seeking the source of the Ishikari River. He also surveyed the oil fields in Niigata, partly at his own expense when the government’s funds ran out. By the way, I have never seen a detailed account of Lyman’s journey up the Ishikari River – even the biography by Kuwada Gonpei doesn’t have one. What a pity: it must have been a fascinating journey, and one that can never be repeated.

The following year, Heinrich Naumann (1854–1927), a German geologist attached to the Kaisei Gakkō, climbed Asama. His temper too was said to be volcanic, which cut short his stay in Japan. Otherwise he would certainly have climbed more mountains. But he did get to name the Fossa Magna.

|

| John Milne and an illustration from his book on Mt. Fuji. |

Another geologist, John Milne (1850–1913) visited Iwate, Chokai, Gassan and Aso during his spell in Japan as a foreign advisor, which lasted from 1875 to 1895. He wrote two papers trying to explain the curvature of Mt Fuji’s slopes, a question which still hasn’t been fully answered to this day. Wisely, he gave up on that line of enquiry and concentrated on earthquakes. Today, he is known as “father of the seismograph”.

|

| Ernest Satow and his guidebook. |

Of course, I should have mentioned Ernest Satow (1843–1929) before. As a diplomat, he was among the first foreigners to explore the Japanese mountains – during his first posting from 1862 to 1883, he traversed Okutama, visited Fuji, Asama, Haruna, Akagi, and Nikko-Shirane, crossed Tanzawa, climbed Ontake, Yatsugadake, Hakusan, and Tateyama, and made first British ascents of Nōtori and Ai-no-take in the Southern Alps. And he was a keen amateur botanist, even writing a paper on the cultivation of bamboos.

|

| From a contemporary review of the Satow and Hawes guidebook. |

But he made two more signal contributions to mountaineering in Japan. First, he was the literal father of Takeda Hisayoshi (1883–1972), who became a founder of the JAC and an expert on Japan’s alpine plants. And, secondly, with another Englishman, he compiled a guidebook: A Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan – first published in 1881.

As we shall see, guidebooks are important: they influence where later travellers go and what they see. This one exerted an even more durable sway – it contains a section by William Gowland (1842–1922), a mining engineer, who was the first to talk about high mountains “that might perhaps be termed the Japanese Alps”. And Shiga Shigetaka probably borrowed material from Satow’s guide for his Nippon Fūkeiron – especially the chapter that inspired Kojima’s ascent of Yari.

|

| Mr and Mrs Weston at Kamikochi in 1923. |

That brings us back to Weston. For his travels in Kyushu and Honshu, he used the Satow and Hawes guidebook, now known as “Murray” after its publisher, which he later helped to update. He also used trains where he could – according to Weston himself, there were already more than 3,600 kilometres of railways. So, even in the 1890s, his mountaineering had quite a modern flavour, sped on its way as it was by a detailed guidebook and efficient public transport. All that was lacking was modern maps.

So what happened after the Japan Alpine Club was formed? For a start, JAC members took over the role of pioneers. Kojima Usui identified a “Golden Age” of mountain exploration that lasted until the Army Surveyors published their maps of all the Japan Alps, removing the last shred of mystery from the mountains.

Thus, when Walter Weston traversed Ōtenshō-dake in August 1914, he was following in the footsteps of Kojima and his JAC colleagues, not the other way round. The titles of his two mountain books say it all: “Mountaineering and Exploration…” (1896), followed by “The Playground of the Far East” (1918). By the way, while travelling towards the Northern Alps by train, he was surprised and appalled by the sight of the new oil rigs along the Niigata coast.

|

| View of oil rigs on the Niigata coast. |

So times had changed…

4 comments:

I read the Ryokusokai newsletter link, with the help of google translate. Interesting perspectives on Weston! Ten or so years ago, after reading the Weston obituary in the AJ (https://www.alpinejournal.org.uk/Contents/Contents_1940_files/AJ52%201940%20268-282%20In%20Memoriam.pdf) page 274, I too enquired at the AC about the Fuji kakemono. No-one knew of it or found any record of it. The fact that it is mentioned in Weston's AJ obituary strongly suggests to me that Weston did indeed pass it on to AC. I very much suspect the AC have lost it or it's still rolled up somewhere in the archives, or perhaps it was lost when they moved premises? I think it a little unfair to suggest that Weston hung on to it, no pun intended ;-)

Iain: many thanks for flagging up the obituary - there are many good things it, and I note the bit about the "kakemono". So at least one of things seem to have made it to the Alpine Club. Mmm, interesting. If you have any time to investigate further, it would be interesting to know what became of it ...

Nice one. Wish we'd seen this before undertaking our own little project...

Ted: please feel free to tweak your project with anything from this series that takes your fancy - it should all be public information or secondary sources, anyway. This is only reciprocating the favour, by the way - the next post will include a quotation from Edwin Reischauer's autobiography that Wes put me onto (Thanks, Wes!).

Post a Comment