Captain Scott was cool on colour. The Antarctic hero saw to it that, photographically, his expeditions were documented in black-and-white. If colour illustrations were needed at all, they could come from the deft paintbrush of Edward Wilson, the expedition’s doctor.

Yet, in April 1912, probably just a few days after Scott and Wilson breathed their last, a small Swiss expedition took ship for Greenland. Led by Alfred de Quervain (1879–1927), they made the first west-to-east crossing of the island’s ice cap – and recorded their adventures in a trove of colour images. One of these photographs, now preserved for posterity at the ETH Library in Zurich, captures something of the leader’s rugged and energetic personality:

So how did this expedition immortalise itself in colour, more than two decades before the advent of Kodachrome?

When the Swiss explorers reached Godthaab on Greenland’s west coast, de Quervain records that “We had a chance to use the darkroom of the Greenlander Jon Möller to develop our colour photographs.”

We? Who exactly was it who developed those colour images? Skilled photographers were not lacking on this expedition. Its most senior member, August Stolberg (1864–1945), was also the expedition’s most practised and professional photographer. As early as 1888, he’d hauled his camera around the cathedrals of France for a noted series of handbooks on architectural monuments.

|

| August Stolberg (lower right) with the other members of the Swiss 1912 expedition to Greenland (Wikipedia) |

Appropriately for a photographer, his interests spanned both arts and sciences. He’d studied art history in Munich, Zurich, Bern and Strassburg, then a German city, but also attended lectures in geography and geophysics. From 1900, he was active as a scientific assistant in the meteorological service for Alsace-Lorraine.

With his boss Hugo Hergesell, Stolberg took part in Germany’s first piloted balloon flights for scientific purposes. In May 1900, they flew from Friedrichshafen over the Zugspitze and landed in the Tyrol, thus completing one of the earliest transalpine flights.

Later, Stolberg worked in an international committee for coordinating weather balloon observations, also under Dr Hergesell. It was here, in Strassburg, that he made the acquaintance of Alfred de Quervain, who served as the committee’s secretary up to 1906.

|

| Launching a weather balloon in Greenland, 1912 |

A decade and a half older than de Quervain, Stolberg became a kind of mentor to him. Under Stolberg’s tutelage, the Swiss scientist qualified as a balloon pilot. And in 1909 the two men joined forces to make a first foray to Greenland’s west coast. This experience paved the way for the later expedition. But, as we shall see, he was probably not responsible for the expedition’s colour photos.

In 1912, colour photography was still in its nascent phase. The Lumière brothers of Lyon had patented a mosaic-screen process in 1903, launching it commercially in 1907. Their Autochrome plates continued to be the most widely used way of making colour prints until colour films appeared during the 1930s. And it was an Autochrome that was developed in Godthaab.

Although Autochromes needed much longer exposure times than black-and-white emulsions, one of the expedition’s photographers took at least one more on their journey up Greenland’s west coast. Later in April, the party interrupted their sea voyage at Sarfanguak, where they stayed with David Ohlsen, the local representative of the Danish authorities.

Ohlsen would be critical to the Swiss expeditioners’ success. He had taken upon himself the almost impossible task of teaching them how to drive dog sledges – in less than a month. Yet, in a bootcamp lasting just ten days, he did manage to instil sufficient polar travel skills to ensure their survival.

The company of Ohlsen’s daughters meant a lot to the expeditioners: “Agatha and Igner helped or entertained us with their harmonica playing, a talent possessed by David Ohlsen too,” records de Quervain.

The above Autochrome photo of Igner Ohlsen was made during this visit. An image of Igner would be one of just two colour illustrations to grace the first edition of de Quervain’s book about the ice cap crossing. But, as we shall see, it would not be this one.

The photographer who brought that wry smile – or is it a grimace – to Igner’s lips was Wilhelm Jost (1882–1964). As de Quervain records, “Jost was also an excellent colour photographer, whose most thankful subjects were the Holstensborg beauties in their flamboyant costumes.”

As a glaciologist and expert alpinist, Jost’s role was to stay behind on Greenland’s west coast, together with Stolberg and Professor Mercanton. While de Quervain’s four-man party dashed across the ice cap, this scientific triumvirate would make weather observations and survey a glacier. And to document the latter, Jost would wield a large-format camera to expose plates measuring a generous 13 by 18 centimetres. Researchers are still using some of these images today, as they assess the melting rate of Greenland’s coastal glaciers.

|

| Wilhelm Jost (seated, right) with other members of the "Western Party" and two porters, 1912 |

By early August, de Quervain’s traverse party had completed their traverse, reaching safety at the settlement of Angmagssalik on the east coast. Driving their sledges some 640 kilometres in just 31 days, they had worthily vindicated themselves as graduates of Ohlsen’s crash course in dog handling. Unsurprisingly, they had no time to take Autochromes along the way.

After the traverse team and Professor Mercanton had returned to Europe, Stolberg and Jost overwintered at the Danish Arctic Station in Godhavn. There they completed their series of weather observations, making a total of 120 weather balloon launches into the winter night skies. One balloon, they estimated, may have reached the staggering altitude of 39,000 metres.

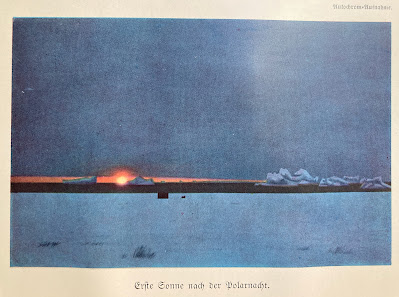

Jost also continued to experiment with Autochrome photography. It was during this sojourn that an Autochrome photo showing the first sunrise after the polar night was taken. In 1914, this photo supplied the colour frontispiece for the first edition of de Quervain’s book:

|

| Frontispiece to Alfred de Quervain's Quer durchs Grönlandeis (1914) |

Jost’s sunrise – at least, we assume it was Jost’s – may be one of the most compelling colour images to be made on a pre-1914 polar expedition. Although there could be some competition for that appraisal.

|

| Autochrome image by Herbert Ponting, 1911 (National Gallery of Australia) |

Captain Scott’s talented and energetic photographer Herbert Ponting also experimented with Autochrome. Taken on 1 April 1911, his study of the evening afterglow from Camp Evans (above) makes the most of the dreamy, hazy quality of this new medium.

Alas, Captain Scott was not impressed ...

No comments:

Post a Comment