“Was that a bear?” I ask the Sensei, somewhat superfluously. “Probably,” she replies, sounding unimpressed, as if dealing with just another unruly pupil from her middle school teaching days. I am reassured: if that bear happens to be sporting a non-standard haircut, it will be ill-advised indeed to come out from that thicket.

Plodding on upwards under the dripping beeches, I start to see where the bear is coming from. For half a century, the animal – or its forebears – had this ridge to itself. The path for humans washed out in 1937 and wasn’t restored until the 1980s. Even today, it is far less frequented than the standard route up Hakusan, for reasons we will soon appreciate.

The bear has made its point. This is not a hiking trail. Rather, it is a Zenjōdō, a Way of Righteousness. And those who tread it will undergo various tests and tribulations until they reach some higher level of awareness. Or fall by the Wayside. The latter outcome can’t be ruled out, laden as we are by four or five litres of water, sleeping bags and cooking gear.

Hakusan, a sacred mountain, has three Zenjōdō, but the one we are attempting, from the Kaga side, is much longer and more rugged than the modern "normal route" from the west. We are heavily loaded because – unless we opt for trail-running – we’ll need to stay in the Oku-Nagakura bivouac hut, which is innocent even of a water source. The pack is starting to become a trial in itself.

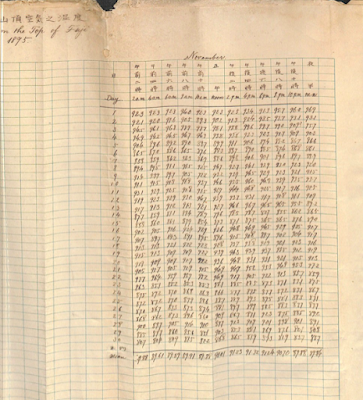

At least the weather front has gone by, even if the clouds haven’t yet cleared. For November, it’s warm. “In the old days,” I observe to the Sensei, “you’d have seen frost pillars poking up out of the ground by now.” Always, people should be careful what they wish for.

We come up to a little shrine, shrouded in mist and watched over by a stand of evergreens – hinoki, says the Sensei, good for making storage chests. The girth and stature of these noble trees suggest what might have been if too many hadn’t been made into chests and temple pillars in centuries gone by.

The path levels out, stray sunbeams slant in below the drifting cloudwrack, and even our watch altimeters strike an optimistic note: they now read within a hundred metres of the hut’s altitude.

Alas, we are deluded: just as the digital readout says we are almost there, the path sinks away towards a deep col and, like pachinko players on a bad streak, we give up all of the last half-hour’s winnings. I recall reading somewhere that Hakusan is a “dissected edifice”. Naruhodo, like John Pierpoint Morgan’s stock market, this ridge will go up. And it will go down. But not necessarily in that order.

The hut is reached as the light starts to fade. The Sensei agrees that it’s been years since we’ve done anything like this. Nevertheless, she has the stove lit and the supper cooking before I have even managed to recombobulate myself. We slurp noodles by the light of our head-torches; I’d forgotten how quickly it gets dark in November around here.

Stepping outside after supper to address the bank of panda grass that fringes the hut, I find myself under a starry sky, Orion stretching up to the winter zenith, as he always did. The mountains have vanished into a void even darker than the sky, relieved only by the faraway strip of lights along the coastal plain. It’s going to be a cold night up here at 1,700 metres …