“We can be satisfied with our scientific results…” wrote the Swiss meteorologist Alfred de Quervain in 1913, a year after leading the first expedition to cross Greenland’s ice cap from west to east. And regarding Greenland’s weather, geography and glaciers, there was every reason to be proud of their findings. Indeed, climate scientists still refer to them today.

|

| A plate from Hans Hössli's paper on craniological studies |

When it comes to craniology, though, could it be that a chill creeps into de Quervain's tone? The expedition doctor, Hans Hössli, had assiduously investigated the physiology of Greenland’s indigenous people. But his research gets but the briefest of mentions in Quer durchs Grönlandeis, the popular book about the Greenland adventure that de Quervain published in 1914:

In another field, our anthropological measurements and collections added some welcome information, especially about the usually inaccessible east coast. The data on the craniums of the pure Eskimo race are particularly valuable, and are already being evaluated elsewhere.

To find out more, one needs to delve into the stacks of Zurich’s Zentralbibliothek. There, with luck, can be retrieved a yellowing copy of Ergebnisse der Schweizerischen Grönlandexpedition = Résultats scientifiques de l'expédition suisse au Groenland: 1912-1913. Published in December 1920, this is the volume in which, a world war after they returned to Switzerland, the expeditioners set down their scientific results for posterity.

Towards the back of this tome is the chapter by Dr Hans Hössli MD. The illustrations give the game away, as do the accompanying tables of figures. This is an exercise in measuring people’s skulls, particularly those of people living on the “usually inaccessible” east coast of Greenland.

But why bother? The clue here is found in the chapter’s introduction. The 1912 expedition, it explains, continued work undertaken on de Quervain’s first expedition to Greenland, in 1909. Footprints, hair samples and “body measurements” were collected from both the east and the west coasts. The work was carried out with the knowledge and approval of “Prof. Schlaginhaufen”.

_AB.1.0873_Schlaginhaufen.tif.jpg) |

| Otto Schlaginhaufen in 1914 (Wikipedia) |

As he saw it, Schaginhaufen’s mission was nothing less than to establish anthropology as a hard science – in contrast to the school epitomised by Franz Boas (1858–1942) in the United States, whose approach tended more in the direction of a cultural or social science discipline.

A hard science needs to draw on hard data. To that end, Schlaginhaufen and his followers sought to define the world’s peoples in terms of their physical dimensions – rather than in terms of “soft” factors such as differences in language and culture. As this required an internationally standardised approach to collecting such data, the Zurich school of anthropology drew up a whole apparatus of definitions and even specialised tools for measuring, say, the dimensions of a human skull.

This helps to explain Dr Hössli’s special interest in collecting skulls from grave sites on the eastern coast of Greenland. In this remote, less inhabited region, he postulated, one would be more likely to find examples of the “pure Eskimo race”, uninfluenced by intermarriage with European or American interlopers, as was commonplace on the island’s more populous west coast.

And it was for this reason, after arriving at Angmagssalik in August 1912, that he made a special trip to small islands south of the settlement. In this, he was accompanied by fellow expedition members Roderich Fick and Karl Gaule plus an interpreter. Excavating ancient graves, presumably without objections from any living inhabitants, the party added 28 more skulls to the doctor’s collection, supplementing the eight he’d already received from a Pastor Rovsing.

As Dr Hössli proudly notes, this was the largest series of skulls so far collected by any western researcher in Greenland, at least from a single site. And then:

In the 1920 report, several pages of data follow, together with illustrations of both skulls and live subjects. And with what results? Summing up, Hössli feels confident in dismissing previous commentators (“DAWKINS, BRINTON, LUBBOCK etc”) who posit a European origin for the natives of Greenland. Rather, he continues:

And the chapter concludes with a compliment to the Danish authorities for their enlightened policies:

A hard science needs to draw on hard data. To that end, Schlaginhaufen and his followers sought to define the world’s peoples in terms of their physical dimensions – rather than in terms of “soft” factors such as differences in language and culture. As this required an internationally standardised approach to collecting such data, the Zurich school of anthropology drew up a whole apparatus of definitions and even specialised tools for measuring, say, the dimensions of a human skull.

This helps to explain Dr Hössli’s special interest in collecting skulls from grave sites on the eastern coast of Greenland. In this remote, less inhabited region, he postulated, one would be more likely to find examples of the “pure Eskimo race”, uninfluenced by intermarriage with European or American interlopers, as was commonplace on the island’s more populous west coast.

And it was for this reason, after arriving at Angmagssalik in August 1912, that he made a special trip to small islands south of the settlement. In this, he was accompanied by fellow expedition members Roderich Fick and Karl Gaule plus an interpreter. Excavating ancient graves, presumably without objections from any living inhabitants, the party added 28 more skulls to the doctor’s collection, supplementing the eight he’d already received from a Pastor Rovsing.

As Dr Hössli proudly notes, this was the largest series of skulls so far collected by any western researcher in Greenland, at least from a single site. And then:

We carefully collected the skulls, packed them painstakingly and took them to Europe. At the Anthropological Institute of Zurich, I was given the opportunity to measure and describe the skulls by the kind courtesy of Prof. Schlaginhaufen. The result of this work is presented in the following report….

In the 1920 report, several pages of data follow, together with illustrations of both skulls and live subjects. And with what results? Summing up, Hössli feels confident in dismissing previous commentators (“DAWKINS, BRINTON, LUBBOCK etc”) who posit a European origin for the natives of Greenland. Rather, he continues:

… we are firmly convinced that the Eskimo are of Mongolian descent, or since the term descent usually expresses a more recent condition, that they represent a basic Mongolian type. Whether this people had its homeland in Asia or North America is irrelevant for us in the first instance. What matters for us is to enquire how this Mongolian type is related to the recent Mongols of Asia.

And the chapter concludes with a compliment to the Danish authorities for their enlightened policies:

Finally, at the end of our work, we should not fail to remark the exemplary way in which Denmark has proceeded, especially in Angmagssalik on the east coast of Greenland, in terms of a colonialism that aims for the natural conservation of a race (“ganz im Sinne eines Rassennaturschutzes”).

“Rassennaturschutz”: a century after they were set down, words like these resonate uneasily. Even in Hössli’s day, some could foresee how such findings might be abused. As early as 1900, Professor Martin, Schlaginhaufen’s predecessor, had warned in his inaugural speech against the growing tendency for anthropological findings to be exploited for nationalistic or political ends.

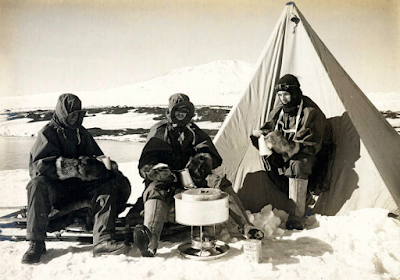

History doesn’t relate what Alfred de Quervain really thought of his doctor’s anthropological investigations, except perhaps for that hint of faint praise in his expedition write-up. But an additional clue might be extrapolated from the plate from Hans Hoessli’s chapter, as shown at the top of this post. The portrait photo shows a hunter by the name of Kitsigajak.

|

| "Old Kitsigajak" as shown in one of the expedition's hand-coloured slides Image by courtesy of the ETH-Bibliothek |

Kitsigajak gets several mentions in de Quervain’s book. He organises the final stage of de Quervain’s sea journey to Angmagssalik, as local people helped to bring the expedition back to human habitation on the east coast. And, in his younger days, he once paddled his kayak two thousand kilometres to southern Greenland and back to buy tobacco. And, finally, he anchors one of the expedition’s most important findings:

To us Greenland was a wondrous revelation. Among the insights which we – or at least I myself – gained is an awareness that the maxims that our civilization takes for granted, namely “faster and faster” and “more and more”, have in fact made fools of us. Do we believe that the quality of our lives is improved tenfold by going ten times as fast, or by hearing and doing ten times as much every day? …. Well, I wonder if that is really the case. For we have now arrived at a limit, beyond which the immutable law of our being will always have their way. That is, if sensations reach us ten times faster, their impression will diminish tenfold, with the result that the faster we live the more impoverished we will become. That is a small truth I have learned from the ice cap, from the midnight sun and the hundreds of little wrinkles in old Kitsigajak’s face. It is another of the results of the expedition that I may not suppress.

For de Quervain, Kitsigajak was an individual, not a specimen. And the Swiss expeditioners knew that they owed much of the success of their Greenland crossing, and probably their lives, to the indigenous techniques, tools, clothing and competence that they'd wholeheartedly adopted.

References

Pascal Germann, «Zürich als Labor der globalen Rassenforschung: Rudolf Martin, Otto Schlaginhaufen und die physische Anthropologie, 1900-1950», in Patrick Kupper, Bernhard Schär (eds), Die Naturforschenden: Auf der Suche nach Wissen über die Schweiz und die Welt 1800–2015, Hier und Jetzt Verlag, 2015.

Alfred de Quervain, Across Greenland's Ice Cap: The Remarkable Swiss Scientific Expedition of 1912, with an introduction by Martin Hood, Andreas Vieli and Martin Lüthi, McGill-Queen's University Press, May 2022.

Alfred de Quervain and Paul-Louis Mercanton, Ergebnisse der Schweizerischen Grönlandexpedition. 1912–1913 (Neue Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, Kommissionsverlag von Georg & Co., Basel, 1920.