Those bottles weren’t just for bivouacs, though. During the Golden Age of alcoholic alpinism, they were equally apt to emerge from the havresac (sic) during the heat of the action. Here is J G Dodson, Member of both Parliament and the Alpine Club, tackling the Col de Miage in 1859:

We were feeling that raging thirst for inspiring which the High Alps can compete with the deserts of Mesopotamia. All the oranges, all the apples, were gone long ago; snow in the mouth brought no relief ; we must have some wine, we said to Cachat, as we paused with him to take breath at the foot of a vertical wall of rock, leaving Bohren and Couttet to go ahead and look out for a road. Cachat produced the last bottle from his store, which I put to my mouth, fondly expecting a good draught of St. Jean. It was strong luscious Muscat, one bottle of which our host had insisted on our taking, tepid with the heat of the sun and with being churned in a havresac: for all that, we drank it down like so much water, but it afforded little relief to one’s thirst. I looked at the ridge far above me, and bethought me of the bitter wish expressed shortly before concerning Mont Blanc by a gentleman toiling up it and in the agony of sinking into deep snow at every step, “You infernal mountain, I should like to have you rolled out and sown with potatoes!”

Dodson’s account appears in the Second Series of Peaks, Passes and Glaciers (1862) edited by that same E S Kennedy who chaired the Club’s inaugural meeting. Perhaps thanks to the emollient effect of the strong luscious Muscat, Dodson subtitles his piece as “A Day in a Health-Trip to the Glaciers”.

Health trip? I hear you snort: drinking while climbing is just plain dangerous. And nobody can deny that a certain degree of risk does attend this heady combination. Take the contretemps that befell one Charles Packe BA, while descending a gorge below the Portillon d’Oo in the summer of 1861:

Our stock of wine was carried in two skin bottles, with the exception of a solitary bottle of champagne, which Barrau had brought from Luchon, and which had already escaped such imminent risk of breaking, that I resolved not to give it another chance. Barrau, not at all unwilling to be relieved from his responsible charge, deposited the bottle in a natural wine cooler formed by the stream, but had scarcely done so when a sharp report announced an involuntary libation to the water nymphs of the place. The bottle had burst into pieces, and the champagne was lost to me for ever; but Barrau, with admirable presence of mind, immediately applied his mouth to a little runlet just below the scene of the catastrophe, and, I believe, pretty nearly recovered his full share of the champagne, though probably in a more diluted state than he would have chosen.

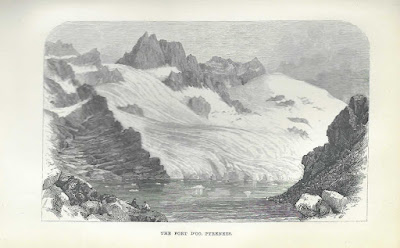

|

| The Porte d'Oo Illustration from Peaks, Passes, and Glaciers, Volume II |

Quite distinct from the danger of involuntary libations, the wine itself could be a source of embarrassment. The experience of J F Hardy on Etna in April 1858 may be taken as typical of such disappointments:

The Doctor had very kindly presented me with a bottle of wine grown upon the mountain; and although I had originally some idea of drinking it on the summit, I felt now that, as it was highly improbable that the rest of the party would be with me there, it would be more in accordance with good fellowship to attack it at once. I announced, therefore, to the group around me the prize I had got, and the treat I intended for them, and taking from my pocket that instrument which no wise traveller is ever without, drew forth the envious cork that separated us from the promised nectar. The bouquet was peculiar, perhaps volcanic; but I passed the cup round to each in turn, commencing of course, with my fair friend. It was received by each with solemnity befitting the occasion. There was silence. The draught was too exquisite to allow of words. My turn came to drink, and I drank.

Imagine then the dismay felt by the good Reverend – for Hardy was a man of the cloth, as well as an AC founder member – when the promised nectar turned out to taste like something that “may be successfully manufactured by drowning a box of lucifers in a bottle of Cape”.

|

| "To enjoy the pleasant air of the peak ..." Detail from above title page of Peaks, Passes, and Glaciers |

Even during the Golden Age, some AC men did question the wisdom of imbibing while ice-climbing. Edward Schweitzer went so far as to interrupt his account of climbing the Breithorn in 1861 to “say here a few words on the injudicious habit of supplying guides and travellers with a heavy supply of food and wine”. And here, under the page rubric of “Injurious Effect of Brandy”, is what he says:

I so entirely subscribe to Professor Tyndall’s opinion, expressed in his admirable and classic work “On the Glaciers of the Alps” that I cannot refrain from repeating it here. He says, “Both guides and travellers often impair their vigour and render themselves cowardly and apathetic by the incessant refreshing which they deem necessary to indulge in on such occasions.” I observed how little food or wine Taugwalder took, and that he preferred the country wine to any stronger drink. This is the habit of all the best guides. With a roll and a piece of chocolate I have sustained myself on many a long climb, husbanding my strength by an even measured pace, and avoiding frequent draughts of water. A piece of sugar will often assuage the painful effects of burning thirst; a raisin or plum will do the same. When water is near, the addition of an effervescent powder is most refreshing but of all beverages, that which soothes me most, when much fatigued, is a slightly sweetened infusion of black tea, mixed with red wine in equal proportions. It is food and drink at the same time, and allays the irritation of the mucous membrane. Butter ought not to be omitted on a mountain excursion; with bread it is often preferable to stringy hard-fibred meat, such as is generally obtained. Brandy ought only to be used as a remedy in case of sudden indisposition. Nothing impairs the nervous powers so much as frequent potations of cognac and water; they give at first an increased feeling of activity, but, “false as the dream of the sleeper,” they assuredly leave the climber more enervated and less fit for work. A case of the kind occurred this season, and might have led to serious consequences. A young Englishman of about twenty-four years of age, the very picture of strength and health, made the passage of the Weissthor from Macugnaga. He was not much accustomed to severe mountain-climbing, and when suddenly confronted by dangerous slopes, he apprehended that his physical powers would not carry him through his appointed task, so he applied himself to frequent draughts of cognac and water, against the warnings of his guides. The result became soon apparent. They had to drag him up by ropes in an exhausted state, endangering in no slight degree the safety of his trusty conductors. In fact, as he told me himself, he had not a notion how he overcame the difficulties and gained the summit: he felt all the time in a helpless stupor.

|

| Monte Rosa from the Gornergrat Illustration from Peaks, Passes, and Glaciers |

Schweitzer had a point of course: when the AC founder William Mathews ascended Monte Rosa in 1856 he was surprised “to see the porters throw themselves onto the snow, and one by one they dropped down exhausted and drunk . . . appearing on the mountain side in continually diminishing perspective”. But, since this was the Golden Age, Schweitzer was not one to take his own advice to excess. Just previous to the diatribe quoted above, he records that his party “partook of a small repast of bread and butter, cold meat, and a cup of Beaujolais”.

Such concerns nothwithstanding, mountaineers who embraced the true spirit of the Golden Age were apt to minimise the obvious risks of alcoholic alpinism. Here, for example, is the Reverend J F Hardy again, this time atop the Lyskamm, one of Zermatt’s trickier four-thousanders, in August 1861:

For somewhat more than half an hour we feasted our eyes with this magnificent panorama, till some one complaining that he felt cold, there was a general cry for more of the Sibson mixture. Perren, who knew the difficulties that were yet to come, was for drinking no more till we were fairly off the aréte; but his prudent counsels were laughed to scorn by the others, who declared it would be a sottise to bring wine to the top of a mountain, and then carry it down untasted. After all two bottles among fourteen were not likely to affect our steadiness very materially; and the slight stimulant would probably do more good than harm. At all events the mixture was taken as before; and then at half an hour after noon commenced the really anxious part of the expedition— the descent of the aréte.

The “Sibson mixture”, Hardy explains, was a “delicious beverage”, invented by the eponymous member of the party and consisting of “red country wine and Swiss champagne combined in equal proportions”. Small wonder that Hardy was fondly remembered by his AC colleagues as “a genial, cheery companion”.

To. conclude: the sorry decline of alcoholic alpinism.

2 comments:

Very entertaining. You've prompted me into delving into Peaks, Passes and Glaciers plus the early Alpine Journals. I think I now know where part 3 is going?

Of those early first ascents, the Schreckhorn appears to be the most alcohol free with there only being reference to the party "taking a drop of brandy all round." Probably v prudent on a such a mountain, as you will know.

Thanks for reading, Iain: no, the Schreckhorn is not a mountain where you'd want to partake much of any "Sibson mixture". But people were having doubts about alcoholic alpinism well before that notable first ascent - watch this space... : )

Post a Comment