The annual audit of snowfall, glacier wastage and permafrost depth in the Swiss Alps, as reported by the Cryospheric Commission of the Swiss Academy of Sciences

At low altitudes, the winter of 2019/20 saw the lowest level of snowfall ever. The loss of ice volume in Swiss glaciers continued in the summer of 2020, during which temperatures reached record highs. The influence of climate change on the cryosphere is very evident.

|

Meltwater channel on the Kanderfirn, 2018

Image by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure

|

Weather and snow: little snow at low altitudes

In the winter of 2019/20, the mountains were covered with snow about two weeks earlier than normal, at the beginning of November. Record snowfalls for November occurred in some locations on the southern slopes of the Alps.

Temperatures then reached record highs from December to February, more than 3°C over the long-term average.The following spring was also clearly too warm and characterised by a lot of sunshine. Below 1,000 metres, precipitation fell mostly as rain during the entire winter half-year. In terms of mean snow depth, this led to the winter with the least snow since measurements began, just ahead of 1989/90 and clearly ahead of 2006/07.

At several stations, for example in Marsens/FR (718m), Einsiedeln/SZ (910m) or Elm/GL (965m), there had never before been so few snow days (days with at least 1 cm of snow). At some low-lying stations on the northern side of the Alps (eg Stans, Basel and Lucerne), no snow at all was recorded for the first time ever.

Above about 1,700 metres, however, snow depths were average in the northern Ticino and in the southern Valais, which was mainly due to the large snowfalls at the beginning of winter and in February.

Very warm between July and September 2020

With the exception of the measuring stations in southern Valais, the snow melted everywhere one to four weeks earlier than normal. The months of July to September 2020 were once again characterised by above-average temperatures. In contrast to the two previous hot summers, snow fell twice in August to just below 2000 metres. On the last weekend of September, the snowfall line on the north side of the Alps fell to as low as about 1,000 metres. Above that, 20 to 80 centimetres of fresh snow were recorded, which is unusual for this time of year, leaving the Alps in a thick white mantle.

|

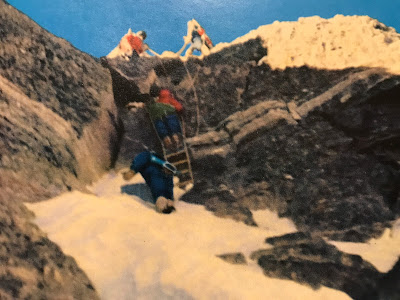

Ice collapse on the Morteratsch Glacier, November 2011

Image by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure |

Glaciers: another 2% of ice volume lost

Between the autumns of 2019 and 2020, glacier loss continued relentlessly, but was somewhat less dramatic compared to the previous three measurement periods of 2016/17, 2017/18, and 2018/19. After average snow amounts were measured at the glaciers' elevations in early May, the summer melt was once again substantial.

Over the entire year, low-lying shallow glaciers (eg the Glacier de Tsanfleuron/VS) showed an average reduction in ice thickness of two metres. Glaciers in southern Valais as well as in Ticino and the Engadin (eg the Findelgletscher and the Ghiacciaio del Basodino) lost only about half a metre in thickness, which can be attributed to the large amounts of snow in early winter as well as the positive effect of the summer snowfalls.

The amount of snow on the Silvretta glacier in Graubünden was about the same as the average for the past decade. This shows that 2019/20 was not an extreme year in terms of the current situation - despite massive losses of about 2% of the remaining glacier volume in Switzerland.

All glacier tongues are receding

The shrinkback of glacier tongues reflects weather conditions over a period of several years rather than the effects of a single year. Climatic conditions affect the position of the tongue with a varying lag depending on the tongue’s location. The fact that the autumn measurements showed a further reduction in the length of glaciers is therefore hardly surprising.

With two exceptions, the glaciers showed a shrinkage of up to 25 metres. Massive recessions of more than 50 metres were seen at Kanderfirn/BE and Sankt Annafirn/UR. In both cases, the tongues have thinned out increasingly in recent years and have now literally disintegrated.

|

Block glacier in Val Sassa, 2021

Image by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure |

Permafrost: 11 metres of thaw layer on the Schilthorn

On the 20th anniversary of the Swiss Permafrost Measurement Network Permos, all permafrost measurement parameters have reached or exceeded the record values posted in 2015.

Due to the early snowfall in autumn 2019, the permafrost accumulated a lot of heat. As a result, surface temperatures were above average, especially during the winter, while annual averages were in the range of the extremely warm years of 2003, 2015 and 2018. The high surface temperatures led to an increase in the depth of the thaw layer – the uppermost metres above the permafrost that thaw each summer.

The previous record values were reached or exceeded everywhere, from 2.8 metres at Flüela/GR to 11 metres on the Schilthorn/BE. The latter is the deepest thaw layer ever measured in Swiss permafrost. Since the beginning of measurements in 1998, the depth at this location has more than doubled. Across Switzerland, the increase on the previous year ranges from a few centimetres to half a metre.

End of the short recovery

The short break in the warming trend that was seen after the snow-sparse winter of 2017 is definitely over. Permafrost temperatures are again similar to or even higher than in the previous record year of 2015. But the permafrost reacts to the changes at the surface only with a long lag time, implying that the warm conditions of recent years have not yet fully penetrated into the depths.

The creep rates of rock glaciers generally follow the trend of permafrost temperatures. Compared with the previous year, they have again increased by an average of 20% on the previous year, exceeding the previous record values from 2015 in some cases.

Text: Matthias Huss, Christoph Marty, Andreas Bauder und Jeannette Nötzli

|

Retreat of the Forno Glacier

Image by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure |

Appendix: New radar system used to measure glacier ice depth

Data on the extent of glaciers and their ice thickness are of interest not just to alpinists but also to forecasters of future glacier retreat and runoff, as well as for the assessment of glacier-related natural hazards. In close cooperation with Swisstopo, the Swiss Federal Office of Topography, the Swiss Glacier Monitoring Network Glamos has therefore compiled a new detailed inventory of the country’s glaciated areas. In 2016, glacier ice covered 961 square kilometres or 2.3% of the country's surface.

In addition to the inventory, a project at ETH Zurich, a new type of helicopter-borne radar was used to measure the ice depth of all larger glaciers. Ice depth measurements are now available along a total track of more than 2,000 kilometers, which makes it possible to determine the total ice volume.

The volume of all Swiss glaciers for the reference year 2016 is estimated at 58.7±2.5 cubic kilometres. Distributed over the area of the whole of Switzerland, this corresponds to a water layer 1.3 metres deep. In line with the extent of the glaciers, ice volume is concentrated mainly in the Bernese and Valais Alps, but considerable volumes are also found in central and eastern Switzerland.

The Great Aletsch glacier – the largest Alpine glacier at just under 80 square kilometres – accounts for 11.7 cubic kilometres of ice. Thus, it alone stores about 20% of Switzerland's glacier ice. By combining these results with annual measurement data, it is possible to determine what proportion of the existing ice has been lost. The numbers are impressive: since 2000, Swiss glaciers have lost just under a third of their remaining ice mass, and in an extreme year the loss can amount to more than 3% in a single year.

The extent of glaciers and their depths can now be can now be viewed directly on the official online map of Switzerland at map.geo.admin.ch. The map shows the most important most important parameters such as area, volume or the maximum and the average ice thickness for the respective glacier.

Source

© Die Alpen, journal of the Swiss Alpine Club, 06 2021 edition. Originally published in German. This is an unofficial translation by MAGE/Captain. Images and charts of original article are not reproduced here.