While the book was being printed, I was several times asked to include in this publication some details of our technical equipment, as our success depended on its thorough preparation. Some of this information is included in the popular account of our expedition, Quer durchs Grönlandeis, and our expedition member Dr H. HOESSLY has independently published a review of "Polar expeditions and their equipment” in the Schweiz. Skijahrbuch (1913), which is essentially an outline of our expedition’s technical gear and our experiences, as originally intended for this volume.

|

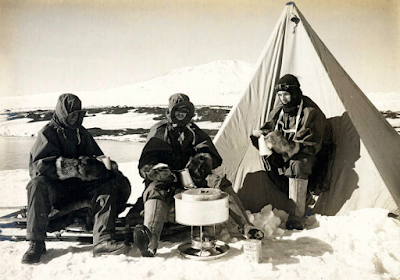

| "Encampment of the traverse party on the inland ice with sledges and dogs, after the snow storm" (photo and caption as published in the original report) |

It remains only to add that our equipment was essentially collected and prepared by the undersigned expedition leader, based on the experience of his journey to the inland ice in 1909 (together with Dr A. STOLBERG and Dr E. BAEBLER), and with the support of the expedition members R. FICK and K. GAULE in the provision of some specially manufactured items, such as tents and sled equipment. H. HOESSLY, in conjunction with my brother Prof. F. DE QUERVAIN, provided the medical equipment. He also served as our “quartermaster” on the trip. My wife also undertook a large share of the work on the equipment.

1. Rations.

The following was our daily ration on the inland ice: pemmican 200 grams (mixture 50% meat powder and 50% fat, and hence a relatively fatty mixture, as recommended to us by SHACKLETON, and produced by BEAUVAIS (now known as the Danske Vin og Konservenfabrik) in Copenhagen, which was consumed mostly as soup mixed with vegetables. Bread 200 grams (as dry ship’s bread, rusks, cakes). Soups 50 grams (dry vegetables, Maggi soups). Sugar 100 grams (as honey and preserves, apple slices). Butter 40 grams (salted Danish butter). Chocolate 50 grams (pure, or meat chocolate, enjoyed while travelling). Cheese 30 grams. Milk (condensed, sweetened, thick or powdered, from Cham, Glockental and Stalden (Switzerland). Meat 100 grams (canned from Lenzburg and Rorschach (Switzerland), smoked meat, bacon. In addition, we tried dog meat on occasion. This was tough and offputting, but successful enough as an experiment. To drink: coffee, tea or milk (no alcohol).

|

| Producers of pemmican: advertisement for the Beauvais company Image by courtesy of Wikipedia |

The total weight, about 900 grams, seems small as compared with the rations of other expeditions. For us, it was quite enough; some of our members who kept eating the full pemmican ration after we arrived on the east coast returned home having put on a noticeable amount of weight. In general, our rations worked out well: we would not change anything, especially the pemmican. Although other expeditions have described it as unpalatable and a necessary evil, we all took to it most warmly and we have missed it since. Indeed, we have used it as the best conceivable food for alpine climbs and recommend it unconditionally.

Feeding the dogs. 350–400 grams of pemmican (allowing for all eventualities, following O. NORDENSKJÖLD'S example, whose pemmican was mixed in the same proportions as ours). In addition, for the first few days, a handful of small dried fish for each dog, during the transition period. This food sufficed; towards the end of the crossing, some dogs got diarrhoea, perhaps from consuming the meat of their companions, as some of the less fit animals had to be slaughtered and fed to the others for efficiency’s sake. (HOESSLY thought that the slaughtered dogs were suffering from muscular tuberculosis).

Meal times. Two hot; after arrival at campsite, pemmican soup, after sleeping, milk etc with supplements. While travelling, short stops to eat; warm drinks from thermos bottles (as long as they stayed intact). Dogs were fed once a day, immediately after arrival; afterwards, their muzzles were tied shut.

|

| A Nansen stove in use by Captain Scott's expedition, 1911 Photo by courtesy of Royal Geographical Society (copyright) |

Cooking apparatus. Nansen stove, with outer jacket and lidded vessel, as produced by The London Aluminium Company, with a Primus petrol stove. The petroleum supply amounted to 30 litres (in various containers in special compartments distributed between the sledge boxes!), of which 8.5 litres were used on the inland ice, which was enough to provide four men with plentiful warm food and drinks for two daily meals (by melting firn snow!) for four weeks. To melt water in case of emergency, a large, thick, black cloth with pockets with snow-filled pockets could be hung on the sunny side of the tent: this produced sufficient meltwater when we tried it out at our highest camp on the ice sheet.

2. Sledges and tent equipment.

For the four expedition members, three Nansen sledges (leaving one man free to go on ahead), from the firm of L. H. Hagen, Christiania, each four metres long, with guardrail and thin steel plate flooring. On the front of each sledge (driver’s seat) was affixed a light limewood box sized and strapped to the sledge, with light fittings for instruments, cooking utensils etc (matches were soldered into tins!). Three or four bags were strapped onto each sledge (those for sleeping bags and clothes must be waterproof).

Tent made of gray-green military tent fabric, to shade the eyes and for heat absorption, main floor space rectangular: 2 x 2.50 metres, with a wedge-shaped projection opposite the entrance, which was pitched against the wind. Shape roof-shaped, ridge height 1.70 metres, supported by four bamboo poles, which ended in cloth caps at the top, and were inserted into 15-centimetre long canvas pockets at the bottom to prevent snow and mosquitoes from entering, and attached inside the tent. Ridge with strong rope sewn in, to keep it taut in a storm. Tent entrance made of light fabric, tube-shaped, which could be tied off from the inside. Tent floor integrated with the rest of the tent; inside, the floor was covered with a completely waterproof sheet, which could also be used as a sledge sail, in conjunction with the tent poles, which fitted together as a mast and yards with the help of some rings and fitted cords. For sailing, two sledges were run side by side.

In the tent, we had four single sleeping bags of young reindeer (winter) fur, weighing about 5 kilograms, which obviously would have sufficed for much lower temperatures.

Against the sun's rays, we were equipped with goggles made of yellow glass, which keeps out the ultraviolet and blue-violet rays without otherwise noticeably reducing the brightness. Thanks to the timely use of glacier ointment (Glacialin, Zeozoon), we hardly suffered from the sun’s effect on the skin, except for the lips; abundant beard growth proved helpful. For the dogs, I had 60 “dog bootees” made, in order to prevent their paws from being abraded on the hard, bare and jagged glacier ice. These found occasional use on the western margins of the ice cap; fortunately they were not needed for long. With each sled, there was a 25–30 metre glacier rope. We had all the necessary material with us, as well as the necessary technical skills, to repair or remake the dog harnesses, which were often devoured by their wearers.

To learn how to drive the dogs, we underwent a thorough apprenticeship of several weeks with the Greenlanders of the west coast (in Sarfanguak and Kuk near Holstensborg, under DAVID OHLSEN) in order to learn, if not the art, then at least the ability to safely handle and manage the 30 dogs we acquired by prior arrangement in Egedesminde, Akugdlit and Jakobshavn. This capability was almost the single most important item of our equipage. The party working on the western edge of the inland ice lived under similar conditions; only their equipment had to be lighter because they couldn’t use dog sledges to help make the often laborious portages, and it could also be lighter because of the warmer temperatures (their tent was made of raw silk, which was inadequate in heavy rain; the sleeping bags made of canvas with flannel linings and with air cushions would have sufficed if they had been properly manufactured). Also, whenever they were not moving, the members of the western party used Greenlandic clothing (ie the hooded Greenlandic "anorak"), which they often still favour for alpine excursions.

(Undersigned)

A. DE QUERVAIN

References

The above note appears in Alfred de Quervain and Paul-Louis Mercanton, Ergebnisse der Schweizerischen Grönlandexpedition. 1912–1913 (Neue Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, Kommissionsverlag von Georg & Co., Basel, 1920.

|

| Nansen sledge with sail, at Holstensborg, May 1912 |

Tent made of gray-green military tent fabric, to shade the eyes and for heat absorption, main floor space rectangular: 2 x 2.50 metres, with a wedge-shaped projection opposite the entrance, which was pitched against the wind. Shape roof-shaped, ridge height 1.70 metres, supported by four bamboo poles, which ended in cloth caps at the top, and were inserted into 15-centimetre long canvas pockets at the bottom to prevent snow and mosquitoes from entering, and attached inside the tent. Ridge with strong rope sewn in, to keep it taut in a storm. Tent entrance made of light fabric, tube-shaped, which could be tied off from the inside. Tent floor integrated with the rest of the tent; inside, the floor was covered with a completely waterproof sheet, which could also be used as a sledge sail, in conjunction with the tent poles, which fitted together as a mast and yards with the help of some rings and fitted cords. For sailing, two sledges were run side by side.

3. Clothing.

Thick woollen clothing (heavy Graubünden loden proved its worth), woollen undergarments, single or double; three each, to change. Warm woollen cap (with the wind always blowing against us, insufficient forehead protection caused permanent discomfiture). In snowstorms, overgarments of light, dense Burberry fabric; welcome some of the time; also for occasional sleeping in the open. For static surveying work at camps in the cold and for longer sledging trips: cloth jackets and hoods lined with South Greenland bird down (anoraks), high double fur boots (kamiks, with seal-skin outers, lined with dog fur). Otherwise, for use with the skis: Laupar boots, only lightly nailed, but used on bare ice with well-fitted crampons. Ash skis with Hvitfeld bindings; the bases of one pair with an awkward grain direction ended up quite rough. Three-metre langlauf-type skis, taken as an experiment, were too fragile and unwieldy when working with the dogs. |

| The traverse party taking a break (Fick, de Quervain, Hoessli) |

In the tent, we had four single sleeping bags of young reindeer (winter) fur, weighing about 5 kilograms, which obviously would have sufficed for much lower temperatures.

Against the sun's rays, we were equipped with goggles made of yellow glass, which keeps out the ultraviolet and blue-violet rays without otherwise noticeably reducing the brightness. Thanks to the timely use of glacier ointment (Glacialin, Zeozoon), we hardly suffered from the sun’s effect on the skin, except for the lips; abundant beard growth proved helpful. For the dogs, I had 60 “dog bootees” made, in order to prevent their paws from being abraded on the hard, bare and jagged glacier ice. These found occasional use on the western margins of the ice cap; fortunately they were not needed for long. With each sled, there was a 25–30 metre glacier rope. We had all the necessary material with us, as well as the necessary technical skills, to repair or remake the dog harnesses, which were often devoured by their wearers.

|

| Lead dogs of the team, Silke and Mons (?) Greenland inland ice, June/July 1912 |

To learn how to drive the dogs, we underwent a thorough apprenticeship of several weeks with the Greenlanders of the west coast (in Sarfanguak and Kuk near Holstensborg, under DAVID OHLSEN) in order to learn, if not the art, then at least the ability to safely handle and manage the 30 dogs we acquired by prior arrangement in Egedesminde, Akugdlit and Jakobshavn. This capability was almost the single most important item of our equipage. The party working on the western edge of the inland ice lived under similar conditions; only their equipment had to be lighter because they couldn’t use dog sledges to help make the often laborious portages, and it could also be lighter because of the warmer temperatures (their tent was made of raw silk, which was inadequate in heavy rain; the sleeping bags made of canvas with flannel linings and with air cushions would have sufficed if they had been properly manufactured). Also, whenever they were not moving, the members of the western party used Greenlandic clothing (ie the hooded Greenlandic "anorak"), which they often still favour for alpine excursions.

(Undersigned)

A. DE QUERVAIN

References

The above note appears in Alfred de Quervain and Paul-Louis Mercanton, Ergebnisse der Schweizerischen Grönlandexpedition. 1912–1913 (Neue Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, Kommissionsverlag von Georg & Co., Basel, 1920.

Copy of original report and accompanying images provided by kind courtesy of the ETH-Bibliothek, Zurich.

Quer durchs Grönlandeis, Alfred de Quervain’s book about the expedition, has recently been republished in English as Across Greenland's Ice Cap: The Remarkable Swiss Scientific Expedition of 1912, with an introduction by Martin Hood, Andreas Vieli and Martin Lüthi, McGill-Queen's University Press, May 2022.

Quer durchs Grönlandeis, Alfred de Quervain’s book about the expedition, has recently been republished in English as Across Greenland's Ice Cap: The Remarkable Swiss Scientific Expedition of 1912, with an introduction by Martin Hood, Andreas Vieli and Martin Lüthi, McGill-Queen's University Press, May 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment