If you want to get to know somebody well, it’s best to visit them at home. And if that somebody is Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740–1799), who instigated the first ascent of Mt Blanc, the best place to start is probably the Musée d'histoire des sciences in his home city of Geneva. As the holder of many of de Saussure’s papers and memorabilia, the museum is currently using these to mount an exhibition on La montagne, laboratoire des savants.

|

| De Saussure's party scales Mt Blanc in August 1787 |

Taking up the entire top floor of the museum’s repurposed villa, the exhibition all but brings de Saussure back to life.

Visitors are received first by his frock coat and hobnailed shoes – there wasn’t much in the way of crampons in those days – and then by his devoted wife Albertine, ably re-enacted in a video display. While she reads out their correspondence, a light beam traces out her husband’s journeys of geognostic discovery on a relief map of the Alps in front of her.

This son et lumière notwithstanding, Horace-Bénédict isn’t allowed to hog the show. As promised in the exhibition’s title, savants are celebrated in the plural. Some were de Saussure’s predecessors: a display of antiquarian books includes those of alpine pioneers in German-speaking Switzerland such as Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733), who famously documented the dragons of the Alps.

For de Saussure, the most formative of these Swiss influencers were probably Gottlieb Sigmund Gruner (1717-1778), whose multivolume work on Die Eisgebirge des Schweizerlandes moved him to learn German, and Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777), celebrated throughout Europe for his lengthy poem on the Alps.

But it was more for Haller's botanical expertise that de Saussure looked to him. When the younger man visited Chamonix for the first time – this was in 1760 – his main aim was to collect plant specimens for Haller. But the magnificent views sparked de Saussure’s interest in finding a way to the top of Europe’s highest mountain. And the rest is history…

This prompted your correspondent to muse that, to get the measure of Mt Blanc more or less accurately, it took a joint Genevan-British collaboration. And to wonder how present-day Shuckburghs and de Saussures are going to fare in the face of take-back-control policies that stifle international cooperation. Outside the museum’s front door a drab December afternoon awaited. Across the lake, Mt Blanc was quite lost to view.

The exhibition La montagne, laboratoire des savants runs until 23 April 2023 at the Musée d'histoire des sciences, Geneva.

References

Musée d'histoire des sciences, La montagne, laboratoire des savants: Catalogue d’exposition

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Voyages dans les Alpes, edited and introduced by Julie Boch, Georg, Geneva, 2002

Sir Arnold Lunn, The Swiss and Their Mountains: A Study of the Influence of Mountains on Man, Rand McNally, 1963

|

| What the well-dressed alpinist wore in 1787 |

Visitors are received first by his frock coat and hobnailed shoes – there wasn’t much in the way of crampons in those days – and then by his devoted wife Albertine, ably re-enacted in a video display. While she reads out their correspondence, a light beam traces out her husband’s journeys of geognostic discovery on a relief map of the Alps in front of her.

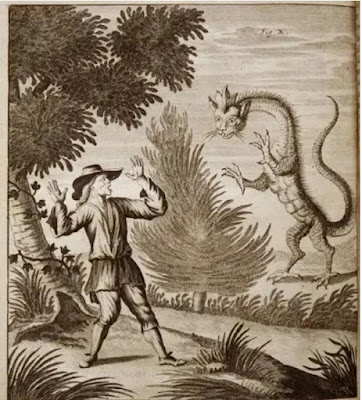

This son et lumière notwithstanding, Horace-Bénédict isn’t allowed to hog the show. As promised in the exhibition’s title, savants are celebrated in the plural. Some were de Saussure’s predecessors: a display of antiquarian books includes those of alpine pioneers in German-speaking Switzerland such as Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733), who famously documented the dragons of the Alps.

|

| Strange encounter near Sargans by courtesy of Scheuchzer |

For de Saussure, the most formative of these Swiss influencers were probably Gottlieb Sigmund Gruner (1717-1778), whose multivolume work on Die Eisgebirge des Schweizerlandes moved him to learn German, and Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777), celebrated throughout Europe for his lengthy poem on the Alps.

|

| A glacier as seen by Gottlieb Sigmund Gruner |

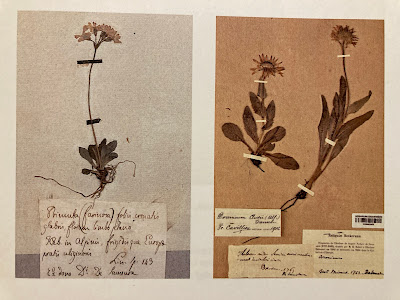

But it was more for Haller's botanical expertise that de Saussure looked to him. When the younger man visited Chamonix for the first time – this was in 1760 – his main aim was to collect plant specimens for Haller. But the magnificent views sparked de Saussure’s interest in finding a way to the top of Europe’s highest mountain. And the rest is history…

|

| From the pages of De Saussure's pressed plant collection |

Next come exhibits on de Saussure’s contemporaries. These include André-César Bordier (1746-1802), whose Voyage pitoresque aux glaciers de Savoye set out one of the first theories to explain how glaciers flowed, Marc-Théodore Bourrit (1739-1819), the tireless promoter of Mont Blanc, and Louis Jurine (1751-1819), who assembled such a vast array of alpine minerals and fossils that his collection ended up at the Sorbonne.

Successors get a mention too. Here is a fine portrait of the astronomer Marc-Auguste Pictet (1752-1825), who took over from de Saussure as professor of natural philosophy at the Academy of Geneva when the older man’s health failed. There was Alphonse Favre (1815-1890), who published a three-volume geological study on the Mt Blanc range. In search of ground truth, he climbed extensively and later helped to found the Swiss Alpine Club, also serving as one of its first presidents.

Successors get a mention too. Here is a fine portrait of the astronomer Marc-Auguste Pictet (1752-1825), who took over from de Saussure as professor of natural philosophy at the Academy of Geneva when the older man’s health failed. There was Alphonse Favre (1815-1890), who published a three-volume geological study on the Mt Blanc range. In search of ground truth, he climbed extensively and later helped to found the Swiss Alpine Club, also serving as one of its first presidents.

|

| Alpine folding as modelled by Alphonse Favre |

Lastly there was the great Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), who visited Chamonix with de Saussure’s magnum opus, the Voyages dans les Alpes, in hand (presumably only one volume at a time). Later, von Humboldt undertook his own scientific ascents, setting a world altitude record (at least for Europeans) during an attempt on Chimborazo in June 1802. De Saussure’s Voyages also furnished James Hutton (1726-1797) with some key geological evidence that he needed to nail down his Theory of the Earth (1785).

By now, your reporter was getting the picture. De Saussure didn’t work in a silo: instead he corresponded, hobnobbed and networked across the length and breadth of Europe. If he mounted higher than others – to borrow a bon mot from an eminent British natural philosopher – this was because he climbed on the shoulders of giants.

Speaking of the Brits, they figure quite prominently in this exhibition. Up on the wall are portraits of William Windham (1717–1761) and Richard Pococke (1704–1765), who were among the first outsiders to tour and publicise the glaciers of Chamonix, making their visit nearly two decades before de Saussure.

De Saussure was well-known in English circles. Accompanied by Albertine, he had travelled round the country in 1768-69, visiting mines, universities and men of science and culture such as Sir Joseph Banks and Lord Palmerston, father of the prime minister. It may have been during this stay that he acquired from the workshop of John Dollond, a master optician, the fine achromatic telescope that is displayed on the museum’s ground floor.

By now, your reporter was getting the picture. De Saussure didn’t work in a silo: instead he corresponded, hobnobbed and networked across the length and breadth of Europe. If he mounted higher than others – to borrow a bon mot from an eminent British natural philosopher – this was because he climbed on the shoulders of giants.

|

| Richard Pococke in oriental dress Image by courtesy of Jean-Etienne Liotard, via Wikipedia |

Speaking of the Brits, they figure quite prominently in this exhibition. Up on the wall are portraits of William Windham (1717–1761) and Richard Pococke (1704–1765), who were among the first outsiders to tour and publicise the glaciers of Chamonix, making their visit nearly two decades before de Saussure.

De Saussure was well-known in English circles. Accompanied by Albertine, he had travelled round the country in 1768-69, visiting mines, universities and men of science and culture such as Sir Joseph Banks and Lord Palmerston, father of the prime minister. It may have been during this stay that he acquired from the workshop of John Dollond, a master optician, the fine achromatic telescope that is displayed on the museum’s ground floor.

|

| An optic of distinction from the atelier of John Dollond |

The English reciprocated these visits. In the summer of 1776, the polymathic Sir George Shuckburgh invited de Saussure on an excursion to a hill near Geneva in order to estimate the height of Mont Blanc. By triangulation, Shuckburgh arrived at a figure of 2,451 toises (equivalent to 4,779 metres), rather close to the altitude of 4,778 metres that de Saussure himself obtained just over a decade later, when he boiled up his thermometer on the summit.

|

| De Saussure's alcohol stove front-runs the MSR by 200 years |

This prompted your correspondent to muse that, to get the measure of Mt Blanc more or less accurately, it took a joint Genevan-British collaboration. And to wonder how present-day Shuckburghs and de Saussures are going to fare in the face of take-back-control policies that stifle international cooperation. Outside the museum’s front door a drab December afternoon awaited. Across the lake, Mt Blanc was quite lost to view.

The exhibition La montagne, laboratoire des savants runs until 23 April 2023 at the Musée d'histoire des sciences, Geneva.

References

Musée d'histoire des sciences, La montagne, laboratoire des savants: Catalogue d’exposition

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Voyages dans les Alpes, edited and introduced by Julie Boch, Georg, Geneva, 2002

Sir Arnold Lunn, The Swiss and Their Mountains: A Study of the Influence of Mountains on Man, Rand McNally, 1963

|

| Summoning up the very shades of H-B de Saussure |

No comments:

Post a Comment