The Jungfraujoch lies almost three and a half kilometres above sea level. Staring down from here into the cloud-filled bowl of the Konkordiaplatz, I saw that conditions were less than ideal for skiing solo over Switzerland’s largest glacier. A burly figure standing nearby must have read my mind. “Come with us,” he said, “we’ve got a rope.”

|

| View towards Konkordiaplatz from the Jungfraujoch (3,463m). Photo by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure. |

On the train home, after a pleasant day’s ski-tour through the Bernese Alps, we fell into conversation. My benefactor turned out to be a prominent sekiwake of Basel’s alpinistic community. And he outed himself as a fan of Murakami Haruki, having read pretty much everything the author has published.

I start with this episode to underline that Murakami fans are everywhere (I’ve climbed the Mönch with another, also in so-so weather). But, world-renowned as he may be, the novelist doesn’t merit a flicker of recognition in Mizumura Minae’s The Fall of Language in the Age of English – in which, as far as I can see, she does not mention him by name, or even so much as hint at his existence. Well, this is a rum go.

The original version of Mizumura’s book came out in 2008 with the title of Nihongo ga horobiru toki: Eigo no seiki no naka de – which might be rendered as the Fall of Japanese during the Era of English. Tens of thousands of copies were sold; the book ranked top on Amazon Japan and it won the Kobayashi Hideo Award, named for one of the Hyakumeizan author’s climbing companions. The English translation, with a slightly amended title, appeared in 2015.

Mizumura is refreshingly controversial. Starting with the observation that translations from a universal language (say, Chinese) helped to kick-start literatures in national tongues (say, Korean or Japanese), she asks what effect the new global universal language – English – will have on these national languages and literatures. And she argues that both the languages and the literature will find themselves impoverished.

The book starts with a flashback to an international writing program in Iowa. The experience is less than satisfactory. So far from being oppressed by the English language, many of the participants can barely communicate in it. So the time passes unprofitably for Mizumura, who is fluent in English having spent her high school and university years in the United States. After the program ends, she meets a friend who bemoans the current state of Japanese literature. It’s all crap, they agree.

The second chapter deals with the French language, and how it gradually lost its groove as an international language. Yet, when she entered Yale, it was French literature that Mizumura chose as a major, thus following in the footsteps of many a Japanese intellectual, including the Hyakumeizan author himself and at least two of his climbing companions and fellow literati, Kon Hidemi and the aforementioned Kobayashi Hideo. Alas, Mizumura concludes, French is now “in the same sorry camp” (her words) as Japanese.

But perhaps the lady protests too much. Indeed, the title of her fifth chapter – "The Miracle of Modern Japanese Literature" – almost undercuts her argument. The thesis here is that the stress of encountering Western languages and literature forced the yokuzuna of Meiji and Taishо̄ letters to create a new way of writing. And in this they succeeded magnificently.

Everyone knows about Natsume Sōseki’s love-hate relationship with English literature – indeed, echoes of his travails in London have reached as far as this blog. And he probably voiced the predicament of Meiji-era writers more eloquently than most, lamenting that they had experienced a “sudden twist” away from their culture’s roots in a Sino-centric civilisation.

Mizumura shows that this deep engagement with the West extended across the whole literary landscape. Futabata Shimei, for example, who wrote Ukigumo (Floating Clouds), Japan’s first modern novel in 1887, was “thoroughly schooled” in Russian and its literature.

In the next generation, there was Akutagawa Ryūnosuke (1892–1927), who not only climbed Yarigatake in his youth but “read an astounding amount of English at an astounding speed”: he is said to have despatched an English version of War and Peace in four days.

And there was Nakazato Kaizan (1885–1944), who was an avid reader of Victor Hugo in English translation. Incidentally, his most famous work, the “long Buddhist novel” of Daibosatsu tōge (1929) gets a mention in the very first sentence of the relevant chapter in Fukada Kyūya’s Nihon Hyakumeizan.

As a result, writes Mizumura, “Japan became a nation so literary that it would have been the envy of all literature-loving people of the world – if only they had known!”. If only they had known? For it was only in 1968, Mizumura clarifies, when Kawabata Yasunari won the Nobel Prize, that Japanese literature finally attracted the world’s attention, a full century after the Meiji Restoration.

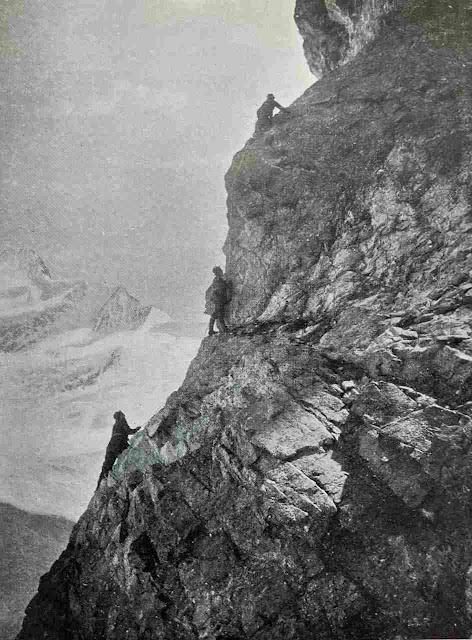

|

| Summit ridge of the Mönch: Murakami fans are everywhere. Photo by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure. |

The original version of Mizumura’s book came out in 2008 with the title of Nihongo ga horobiru toki: Eigo no seiki no naka de – which might be rendered as the Fall of Japanese during the Era of English. Tens of thousands of copies were sold; the book ranked top on Amazon Japan and it won the Kobayashi Hideo Award, named for one of the Hyakumeizan author’s climbing companions. The English translation, with a slightly amended title, appeared in 2015.

Mizumura is refreshingly controversial. Starting with the observation that translations from a universal language (say, Chinese) helped to kick-start literatures in national tongues (say, Korean or Japanese), she asks what effect the new global universal language – English – will have on these national languages and literatures. And she argues that both the languages and the literature will find themselves impoverished.

The book starts with a flashback to an international writing program in Iowa. The experience is less than satisfactory. So far from being oppressed by the English language, many of the participants can barely communicate in it. So the time passes unprofitably for Mizumura, who is fluent in English having spent her high school and university years in the United States. After the program ends, she meets a friend who bemoans the current state of Japanese literature. It’s all crap, they agree.

The second chapter deals with the French language, and how it gradually lost its groove as an international language. Yet, when she entered Yale, it was French literature that Mizumura chose as a major, thus following in the footsteps of many a Japanese intellectual, including the Hyakumeizan author himself and at least two of his climbing companions and fellow literati, Kon Hidemi and the aforementioned Kobayashi Hideo. Alas, Mizumura concludes, French is now “in the same sorry camp” (her words) as Japanese.

|

| Taking a high line on the Louwitor, Bernese Oberland. Photo by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure. |

But perhaps the lady protests too much. Indeed, the title of her fifth chapter – "The Miracle of Modern Japanese Literature" – almost undercuts her argument. The thesis here is that the stress of encountering Western languages and literature forced the yokuzuna of Meiji and Taishо̄ letters to create a new way of writing. And in this they succeeded magnificently.

Everyone knows about Natsume Sōseki’s love-hate relationship with English literature – indeed, echoes of his travails in London have reached as far as this blog. And he probably voiced the predicament of Meiji-era writers more eloquently than most, lamenting that they had experienced a “sudden twist” away from their culture’s roots in a Sino-centric civilisation.

Mizumura shows that this deep engagement with the West extended across the whole literary landscape. Futabata Shimei, for example, who wrote Ukigumo (Floating Clouds), Japan’s first modern novel in 1887, was “thoroughly schooled” in Russian and its literature.

In the next generation, there was Akutagawa Ryūnosuke (1892–1927), who not only climbed Yarigatake in his youth but “read an astounding amount of English at an astounding speed”: he is said to have despatched an English version of War and Peace in four days.

And there was Nakazato Kaizan (1885–1944), who was an avid reader of Victor Hugo in English translation. Incidentally, his most famous work, the “long Buddhist novel” of Daibosatsu tōge (1929) gets a mention in the very first sentence of the relevant chapter in Fukada Kyūya’s Nihon Hyakumeizan.

As a result, writes Mizumura, “Japan became a nation so literary that it would have been the envy of all literature-loving people of the world – if only they had known!”. If only they had known? For it was only in 1968, Mizumura clarifies, when Kawabata Yasunari won the Nobel Prize, that Japanese literature finally attracted the world’s attention, a full century after the Meiji Restoration.

You could take issue with that last judgment. I mean, if the world only woke up to Japanese authors in 1968, Arthur Waley must have been wasting his time when he started translating The Tale of the Genji in the 1920s. What a mercy, then, that he burned up no more than twelve years of his life in completing this thankless task…

This quibble aside, Mizumura’s chapter on the sekitori of modern Japanese literature is a masterpiece – well worth the price of the book on its own. She has twice lectured on this subject at Princeton and it shows.

|

| Crevasse zone on the Louwitor, Bernese Oberland. Photo by courtesy of Alpine Light & Structure. |

However, the following chapter on “The Future of National Languages” ventures into a bit of a crevasse zone. Would someone like Sо̄seki bother to write literature in Japanese today, Mizumura asks – before suggesting that, oppressed by the worldwide sway of the English language, he might prefer to become a scientist.

Well, he might indeed. But, then again, he might equally well run a jazz bar in Tokyo for seven years, and do Japanese translations of short stories by Raymond Carver and Truman Capote, as well as of Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and J D Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, among others, before kicking off a successful career as a writer in his own right …

The case of Murakami Haruki hints that the status of English as a universal language may not be wholly demoralising for writers in other tongues. But Mizumura doesn’t give much airtime to such thoughts. Rather, she suggests, the closer a language is to English, the greater the risk that the population will become more attuned to contemporary Anglophone culture than to its own heritage.

German is a case in point: “Because writing in English comes easily for users of Germanic languages,” Mizumura writes, “more and more writers might even be tempted to write novels, poems and plays in English with a world audience in mind.” Again, they might indeed. But a visit to any bookstore in the German-speaking world will quickly allay such fears.

Speaking of bookstores, your reviewer just last week dropped into the cramped but well-curated one in Terminal Two at London’s Heathrow airport. Needless to say, Murakami occupied a decent fraction of one shelf, amply supported by a slew of cat and bookshop-related fiction from other Japanese authors, to say nothing of the ikigai books in the lifestyle section. And, placed in pole position close to the entrance, was a table of books by newly translated Korean authors, including last year’s Nobel laureate.

You know, English-speaking writers might like to heed Mizumura-sensei’s parting advice to them, which is to try ‘walking through the doors of other languages’. Otherwise, with all this talent flowing in from Asia, they could well find themselves marginalised one of these days…*

References

Minae Mizumura, The Fall of Language in the Age of English, translated by Mari Yoshihara and Juliet Winters Carpenter, Columbia University Press, 2015.