Review: an exhibition at the Swiss National Museum shows that folk tales have propagated themselves far beyond the alpine valleysLoose scree and steep snow are the least of your problems if you want to cross over to Alp Blengias, an almost deserted valley in the Swiss canton of Graubünden. On a bad day, when the clouds scud low over the ridges, you might also encounter, guarding the pass, a phantom rider on a ghostly palfrey. Just one glimpse, they say, will seal the doom of any wayfarer unlucky enough to meet him. Bearing this tale in mind, I chose a fine day for the traverse but still I wondered - what if ... |

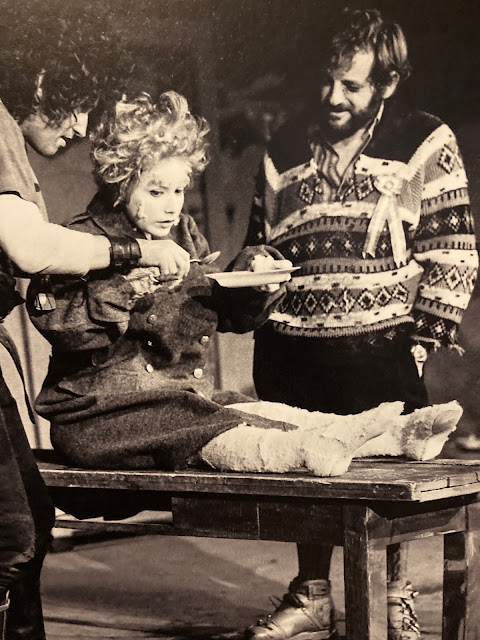

"Sennentuntschi" figurine from the Calancatal, Grisons

Photo: Swiss National Museum |

If you need to know what kind of supernatural terrors you might face in the mountains, then you might want to take in “Sagen aus den Alpen” (Legends from the Alps), the current exhibition at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich. It is guaranteed to send a chill down your spine.

“This exhibition contains photos which may not be suitable for children,” says a sign posted at the entrance. Nor are the curators kidding. A crude doll in a showcase (see image above) is enough to give anybody nightmares. Carved by nameless cowherds on a high pasture in the Calancatal, an obscure corner of Graubünden – that canton again – it almost thrums with a voodoo vibe.

The folktale underlying this exhibit recalls the legend of Pygamalion – the classical sculptor who carved a statue so exquisite that it came to life. But while Ovid’s rendering of this metamorphosis ends happily, the alpine version takes a much darker turn.

|

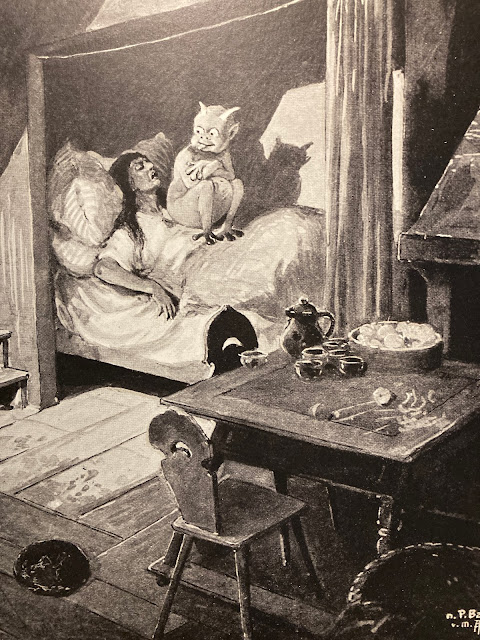

The Sennentuntschi comes to life: from the 1972 stage play

Photo: Swiss National Museum |

Having fashioned a "Tuntschi" out of wood, rags and straw on their lonely alp, the cowherds ("Sennen") treat it like a companion. They speak to her, and some even – as the exhibit’s label euphemistically puts it – “abuse her”. When the creature comes to life, she seems at first to put up with her lot. But when the time comes for the cows to be driven back down to the valley, the Tuntschi exacts a terrible revenge …

In the 1970s, the Basel author Hansjörg Schneider turned the ”Sennentuntschi”story into a successful stage play. But, when aired in 1981, the television version caused an outcry among Switzerland’s more conservative viewers. A so-called Action Committee for Customs and Morals filed a lawsuit against the television company, getting as far as Zurich’s district court before they were forced to desist.

Legends from Graubünden, we surmise, are apt to take a particularly sombre and moralistic turn. The ghostly rider of Blengias is typical of the genre: the protagonist, after cheating his brother out of an inheritance, was condemned to roam eternally in the guise of an equestrian ghost. But the Grey Leagues have no monopoly on alpine gloom.

|

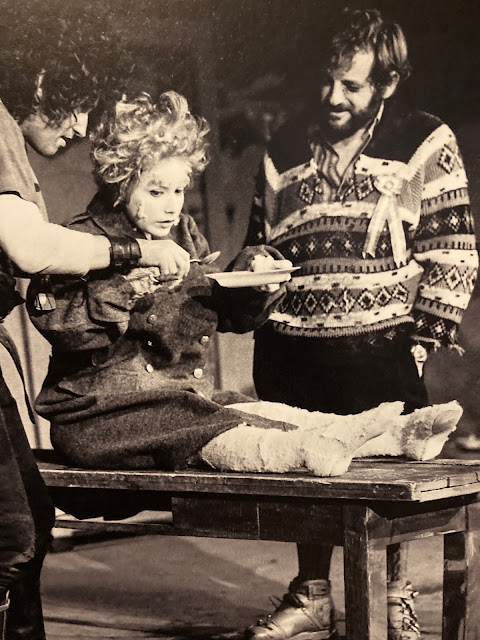

Witches making weather, woodcut by Michael Greyff, 1489

Photo: Swiss National Museum |

Whether or not related to the Sennentuntschi, witches are another of the exhibition’s themes. (Could it be that misogyny is a bit of a thing here?) A broadsheet (below) reports on how three “Hexen” were burned at the stake in 1555 at Derneberg, a locus safely far away from today’s Zurich in both time and space (Lower Saxony). Yet it was just down the road, in Fribourg, and as late as 1731, that a Swiss community most recently turned an alleged witch to ashes.

Books too could be consigned to the flames. For good or ill, legends have enormous staying power. William Tell is a case in point. Although the folk hero is supposed to have inspired the founding of what became the Swiss confederation, in 1291, there is no trace of him in historical records from that time. Yet, when a scholar pointed out in 1760 that the Tell legend bore a suspicious resemblance to a traditional Danish saga, the people of Altdorf publicly incinerated a French edition of his work.

|

William Tell, as depicted (post-Schiller) by Heinrich Jenny in 1868

Photo: Swiss National Museum |

Being outed as a fable did nothing to harm William Tell’s literary afterlife. After Friedrich Schiller dramatised him in 1804, the Tell story went global – there is even a Tagalog version of Schiller’s play.

You could argue that the “Toggeli” has had a similar export success. According to the exhibition’s blurb, this is a spirit that “

usually visits through the night, forcing its way through cracks or knotholes to settle on a sleeper’s chest. It weighs sleepers down or throttles them, and causes them to have nightmares.”

|

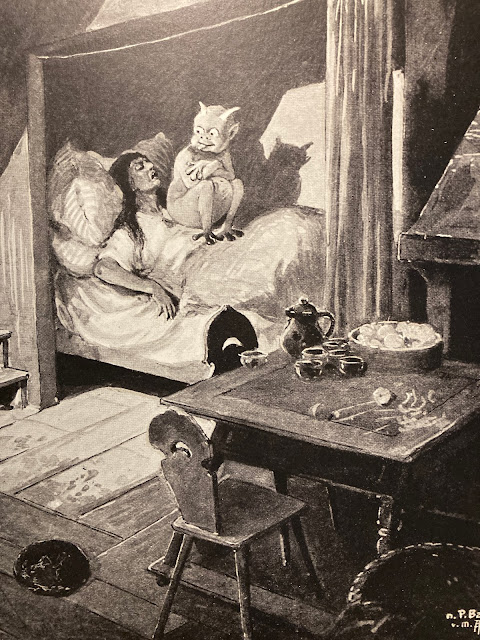

Toggeli in action, illustration by Melchior Annen/Peter Balzers, 1908

Photo: Swiss National Museum |

It was surely a Toggeli that the Zurich-born artist Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) depicted in his painting “The nightmare” (1781), which shows an incubus crouched on a woman’s chest. Mary Shelley was sufficiently impressed to have fashioned a scene after it in her

Frankenstein novel. And Fuseli’s style, if not the picture itself, is said to have inspired the poet and painter William Blake. When it comes to the supernatural, the exhibition suggests, what starts in the Alps might well not stop there.

|

Fuseli's Nightmare, 1781

(Wikipedia) |

Up on the pass to Alp Blengias, I'm happy to say, no phantom rider was lying in wait. Grassy slopes led down into a valley completely deserted, according to the map, except for a single alp hut. Approaching this dwelling, it seemed that somebody had planted beside it a gnarled piece of wood. Or perhaps it was a crudely fashioned statue that, from a distance, looked convincingly like slim human figure standing on one leg, arms raised in the classical yoga pose. Then, as I came closer, the figure started to move….You know, even on a fine summer day in the Alps, you sometimes get to see the strangest sights.

Sagen aus den Alpen, an exhibition at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, runs from 16 December 2022 to 23 April 2023.

References

Peter Egloff,

Pygmalion forever!, Blog zur Schweizer Geschichte, Swiss National Museum

Leo Tuor, Giacumbert Nau: Bemerkungen zu seinem Leben, Roman, Limmat Verlag, 2014.

Also of reference: