3 November: somewhere near Nagano, the morning Kagayaki goes to ground in a tunnel. And there the super-express skulks while the authorities work out where

Kim Jong-un’s latest projectile is going to land. We arrive in Tokyo with half an hour’s delay.

From Shinjuku station, it is necessary to hurry through the badlands of Kabuki-chō to an office near Shin-Okubo. To be late for this meeting would be unthinkable, as the participants are risking a mostly “in person” meeting for the first time in months, if not years.

At 2pm, Dokiya-sensei calls us to order and the proceedings begin. The “Fuyō Nikki no kai” is dedicated to the memory of the meteorologist Nonaka Itaru and his wife Chiyoko, who sojourned on the summit of Mt Fuji in the winter of 1895 to make weather observations, holding out there for almost three months. Everybody at this meeting has some connection with this story, except perhaps for your blogger, who is merely representing the Sensei (otherwise occupied today).

|

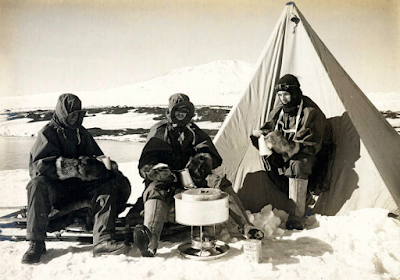

Nonaka Itaru and Chiyoko in mountain garb

(Photo by courtesy of the Nonaka Itaru & Chiyoko Digital Archives) |

As for the “Fuyō Nikki” (Mt Fuji diary) itself, this was the title of Chiyoko’s journal, which she published in a newspaper the year after the mountaintop adventure. A full English translation is forthcoming (watch this space), based on Ohmori Hisao’s definitive joint edition of

Chiyoko’s journal and Itaru’s “Guide to Mt Fuji” (Fuji Annai).

Ohmori-san’s “kaisetsu” (introduction) to that edition is the starting point for anyone interested in the Nonakas’ story – he mentions today that it was based on painstaking trawls for contemporary newspaper articles preserved on microfilm in the Diet Library, conversations with legendary figures in the history of Mt Fuji such as

Fujimura Ikuo, and more than one foray to the mountain in winter. Indeed, to fully appreciate the magnitude of the Nonakas’ achievement, it helps to have experienced Mt Fuji in

full winter conditions.

All this happened a long time ago, yet new details of the Nonaka story are still coming to light – for example, that the Japan Meteorological Association almost certainly admitted Chiyoko to its ranks, showing that Meiji-era scientists might have held remarkably progressive attitudes, at least in this case.

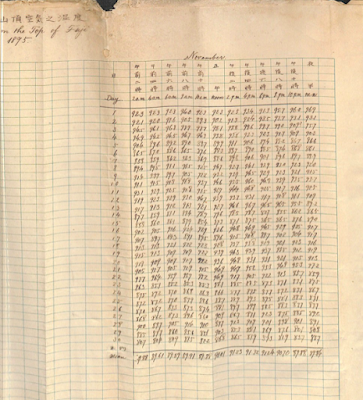

|

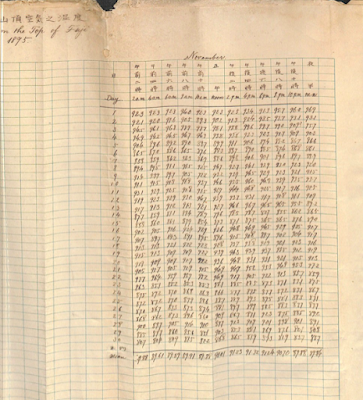

Summit weather readings from November 1895

(Photo by courtesy of the Nonaka Itaru and Chiyoko Digital Archives) |

Across the table, Yamamoto-sensei puts up a slide of the cloth-bound ledger in which Itaru and Chiyoko recorded their weather observations in a neat copperplate hand – amazingly, these records have survived in good condition. No less remarkably, the ledger shows that temperature and barometer readings were set down every two hours, night and day, throughout the twelve-week stay on the mountain – only the wind speed data are incomplete, as the anemometer broke down along the way.

Sadly, no trace of the Nonakas’ tiny summit hut remains. Nakayama-sensei, who also runs the association’s website, brings out a paper model of the present summit station, which was constructed in the early 1960s, and shows us that one of its outlying buildings must have obliterated whatever remained of the Nonakas’ refuge. Oh dear, I’d hoped to find some relics one day.

In Japan, Itaru and Chiyoko have been celebrated – mainly for their exemplary “

gaman” – in a stage play and a full-length movie, as well as several novels and

two TV dramas. The story has seeped out into the English language too, first via contemporaries such as

Lafcadio Hearn and latterly through at least one

scholarly article and a recent feature in

Alpinist magazine.

After being rescued from the frozen mountaintop in December 1895, Nonaka Itaru never did manage to build a bigger and better weather station, as he’d intended. For that reason, some have dismissed him as a dreamer. But his epic eighty-two days atop Mt. Fuji did start people thinking.

One who took note was a

prince of the realm, who as a naval officer considered weather forecasting to be a military imperative. Almost four decades after the couple’s winter sojourn, the government decided to fund an observatory on Mt. Fuji. It was staffed year-round from 1932 to 2004, when automated instruments finally replaced the weathermen.

Not all the meteorologists welcomed that decision. It seemed a pity to waste seven decades of high-altitude experience when good use could still be made of those summit buildings. And so, the very next year, some of their number set up a non-profit organisation for the “Valid Utilization of the Mount Fuji Weather Station”.

Since rebranded simply as the

“Mt Fuji Research Station”, the summit buildings have been validly utilised every summer since 2007. And visiting researchers have published papers on topics ranging from altitude sickness to greenhouse gas concentrations and even the “

sprites” that flash mysteriously upwards from thunderclouds.

With her eyes twinkling over the regulation face mask, our chairperson seems to be a bit of a sprite herself. It seems that the “Fuyō Nikki no kai” is meeting in the offices of the MFRS, and that the memberships of the two committees overlap quite extensively.

I would like to ask Dokiya-sensei about this interesting liminal zone between Art and Science, Adventure and Literature, but, alas, the meeting ends before there is a chance to put the question. And now there is a four-hour Shinkansen journey ahead. Kim Jong-un won’t be accepted as an excuse if I’m unreasonably late for supper …

_AB.1.0873_Schlaginhaufen.tif.jpg)