23 October: dark zeppelins crowd the Hokuriku sky, hinting that it might be wise to spend the day indoors. The nearest unvisited mountain museum – the one in Shinano-Ohmachi – is a full five hours away. But, heck, have RailPass, will travel.

At Matsumoto, while changing trains, there’s just time to pay homage to the bronze statue of Monk Banryū that adorns the station square. Distant Yari-ga-take, the mountain he opened almost two centuries ago, can be glimpsed from the station's overpass. A panorama map helps you find the minuscule pyramid amid the serried peaks of the Japan Alps.

From Matsumoto, a stopping train wends its way northwards towards the Big Town in Shinano. Famous mountains are freeze-framed in the windows as it sashays along the weed-grown tracks.

There’s even a view of the Hyakumeizan’s lost peak, Ariake-yama.

On arrival, it’s a brisk two-kilometre hike to the edge of town. No matter, the rain is still holding off. And there’s little chance of losing your way.

Judging by the generous signage, the Big Town is proud of its Ōmachi Alpine Museum – which may, or may not, be the correct designation in English (the inhouse website is Japanese-only). “The museum was opened in 1951,” says a travel website, adding, a bit cryptically, that it serves “as a location for the regional culture to be further developed.”

A light sweat is further developed by the steep climb up to the museum’s front door, abetted by the warm wind gusting down from the mountains.

But these exertions are amply compensated by the view, which commands a goodly part of the main Northern Alps ridgeline. Few museums are so well positioned vis-à-vis their subject matter.

Those mountains are, of course, the subject. The focus lies squarely on the Northern Alps, leaving Japan’s other eminences to institutions elsewhere. While philosophers may struggle to define a mountain, this museum takes a common-sense approach. It divides its exhibition space into roughly equal tranches between mountains as piles of stone, as habitats for plants and animals, and as places where people make pilgrimages or a living.

The custodian suggests starting on the top floor and working downwards. This brings one first to a room full of rocks and fossils. And herein lies a challenge. While the mountains themselves haven’t changed much since the museum opened its doors, their geological interpretation has evolved beyond recognition.

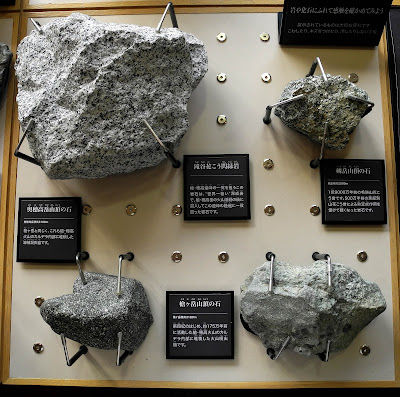

All this means that, if you want to understand how the Northern Alps were built, you’ll have to work a bit harder. I’m bemused, for example, to find a cabinet with samples of granite-like rock from different summits. Neat, but what am I supposed to learn from this?

Fortunately, a video is on hand to outline the current ‘big picture’. The story of the Northern Alps started about 2.6 million years ago when a bleb of magma began to rise from about 30 kilometres below.

About 1.6 million years ago, this upwelling prompted volcanic eruptions on what is now Tateyama and elsewhere.

Then a huge caldera formed between what is now Renge-ga-dake and Kashimayari. Deep drifts of the resulting pyroclastic effusions are still found in the Ōmachi area.

Finally, between 1.4 million and 0.8 million years ago, the nascent Alps were lifted and rotated almost to the vertical.

Strong uplift was attended by vigorous erosion, leaving huge boulders scattered across the valley floor to this very day. Recent glaciations then sculpted the ridges and peaks into their present forms.

Naruhodo: now those rock samples are starting to tell me something. As you work your way from north to south along the mountain chain, closer to the centre of the uplift, they get ever younger. At the northern end, the sedimentary rocks atop Shirouma date back 230 million years, to the beginnings of what one day would become the Japanese archipelago. By contrast, the igneous intrusives that form Hari-no-ki, in the middle of the chain, are less than two million years old. Yet further south, the Hodaka andesites are younger still.

Dropping down to the museum’s middle floor, I’m greeted by a sad-looking kamoshika.

Like every other animal in the room, this goat-antelope is stuffed. Although I prefer my fauna running freely about, the exhibits do testify to Japan’s status as a so-called biodiversity hotspot. Even the squirrels can fly. It would be good to see one of these flit gaily overhead, like a living hearth-rug through the sky.

A corner of the room is given over to the plight of the snow ptarmigan. These friendly birds used to be seen everywhere in the Japan Alps. Alas, their populations have crashed in recent years, as deer and monkeys encroach on what used to be their mountaintop fastnesses. Now that their numbers are down to a few thousand – did I read that right? – efforts are being made to breed them in captivity. A sad and ominous story.

Time is running short: I must start on the next gallery or miss the train home ...

No comments:

Post a Comment